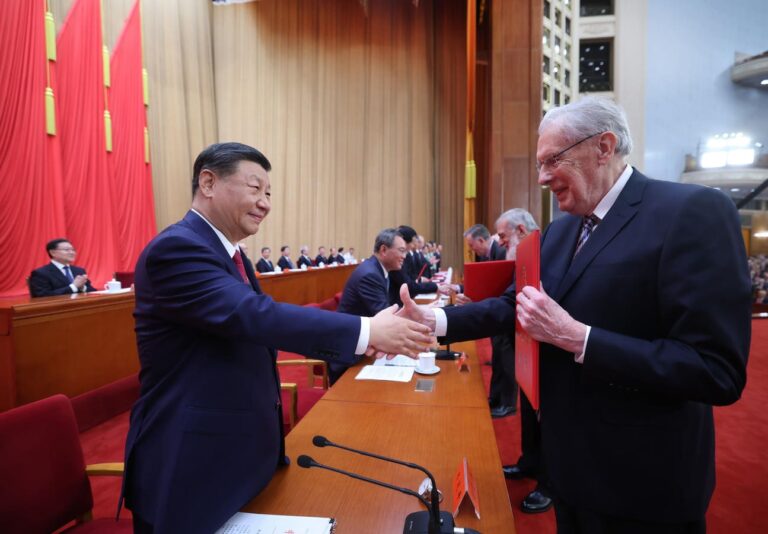

Xi Jinping and other Chinese Communist Party and state leaders, as well as both … [+]

Recent developments highlight the shared interest of the United States and China in bifurcating technological development – a sector that has long benefited from globalization.

Leaders in Beijing and Washington came to two conclusions. The first is simple: innovation is the best and only key to economic growth and geopolitical leadership. The second: to obtain scientific and technological advantage, each country must take vigorous measures in the public and private sectors to compete with (and stand out from) the other.

These dynamics were already at work before the rise of artificial intelligence. The now ubiquitous importance of AI has added an additional dimension to the tech war. The confluence of the “threat” from China and the “risks and opportunities” presented by AI has created an opening for American tech companies to get on the good side of their government—and in the process stifle the AI capabilities of the country where their main competitors are located.

For example, Chinese media have reported that OpenAI will take additional steps to restrict API traffic from countries where its services are not supported (such as China). Chinese competitors like Zhipu AI are looking to fill the void, but another U.S.-based restriction stands in their way: chip controls. U.S. controls on semiconductor exports to China limit the country’s access to the computing power that a domestic company would need to fully replace OpenAI.

More recent moves by the U.S. government have further solidified the strategic direction of creating two separate entities, and the idea is decidedly not equal technological landscapes: one in America and the other in China.

For example, on June 21, the Treasury Department released proposed rules to implement last year’s executive order restricting U.S. technology-related investments in China. According to Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Investment Security Paul Rosen, “President Biden and Secretary Yellen are committed to taking clear and targeted actions to prevent the advancement of key technologies like artificial intelligence by countries of concern. threaten the national security of the United States.

With respect to AI, the proposed rules provide “a prohibition on covered transactions related to the development of any AI system designed for use exclusively or intended for use for certain end uses.” Although this roundabout language alludes to military uses, its vagueness could allow restrictions aimed at more innocuous “end uses” in practice.

As the United States accelerates the Great Tech Divide, Beijing’s leaders are in turn accelerating plans to domesticate innovation — which predate, but have been accelerated by, U.S. punitive measures targeting China’s tech sector . As Xi Jinping said at the National Science and Technology Awards Conference last week, “the scientific and technological revolution and the great power game are closely linked.”

His diagnosis of how China should compete in this context is both comprehensive and short on policy details. He called for integrating science, technology and industry and investing resources in “key areas and weak links”. R&D, according to Xi, should be undertaken in direct response to the bottlenecks China faces in areas such as semiconductors “to ensure the autonomy, security and controllability” of important supply chains. supply.

He advocated that companies work with universities and research institutes (the idea is to ensure that innovative advances have commercial viability and, conversely, that marketable products reflect technological advances).

Xi Jinping also stressed the importance of training talent, a resource on which China has high hopes and over which it arguably has the most control. He called for creating an internationally competitive job market and talent ecosystem and giving science and technology researchers the trust and freedom they need to succeed.

Xi Jinping’s speech only reiterated China’s comprehensive approach to advancing innovation – both for its own economic success And to compete with the United States. Washington’s recent moves toward government and industry integration in recent years represent more of a divergence in the American political context. Its continuation also depends on the next presidential election.

But it makes sense. Whatever one’s view of the goal—beating China in everything at all costs—achieving it will require coordination between the public and private sectors. For now, it seems that the U.S. technology and policy communities are sufficiently aligned to tackle their shared goals, and perhaps achieve them.

But it wouldn’t take much for this alliance of circumstance to dissipate. The unity that China enjoys between party, state, and industry, while not perfect, is far more critical to the overall ability of leaders to maintain power. Coordination is therefore a higher priority and, perhaps, more likely to produce long-term results in the future of the two technological worlds that the leaders of both countries seem ready to deliver.