The big picture

-

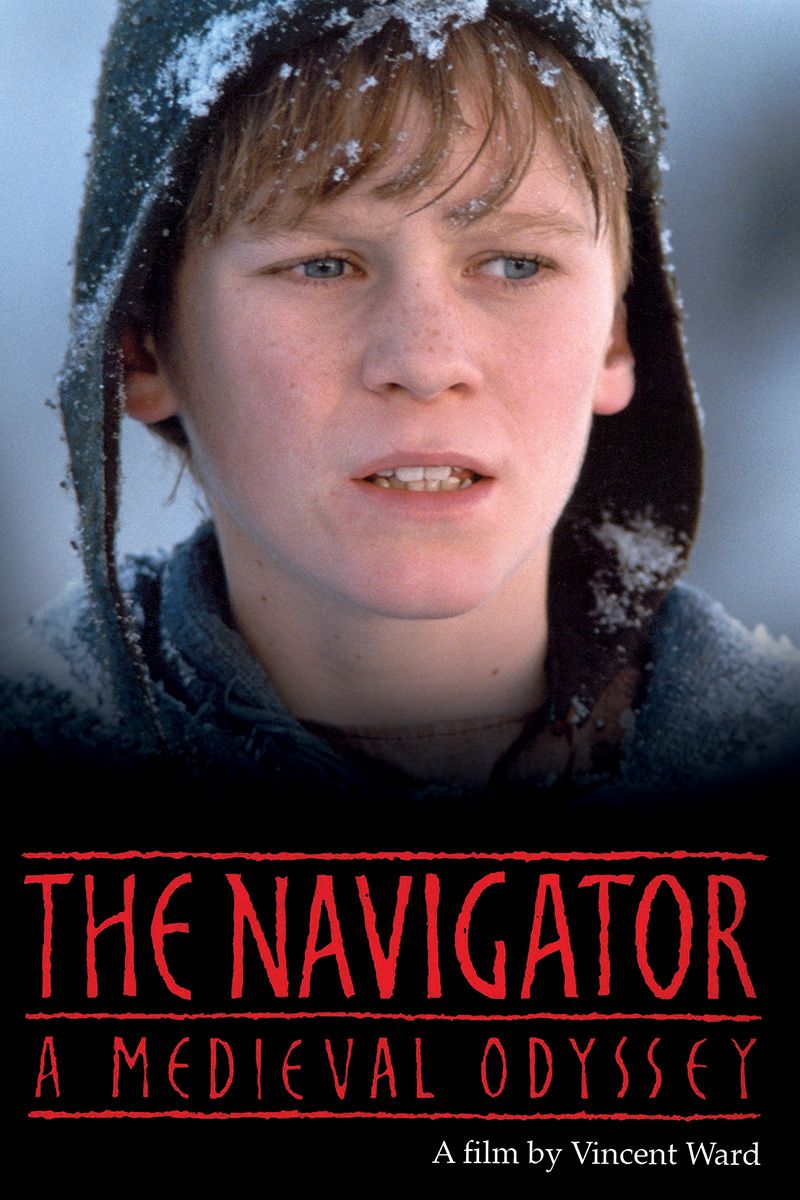

The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey

uses visions and dreams to explore time travel in science fiction and fantasy. - The film’s unique approach to time travel involves a vision of the future in color, contrasting with the black and white of medieval times.

-

The browser

defies genre expectations and explores the futility of time travel, while exploring the social and religious aspects of medieval times.

Using the immeasurable fear and despair of the bubonic plague, Vincent Ward‘s The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey offers a different approach to the age-old tradition of time bending in Science fiction And fantasy films. Creatively ambitious and loaded with religious and societal connotations, The browser complexly uses visions and dreams to warn his characters of impending doom, playing with the audience’s expectations of what is real and what is not. The result is an assortment of filmic images that bend the conventions of time and space, and is arguably essential viewing for those interested in time travel and all its immense possibilities.

The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey

Guided by a boy’s vision, men seeking relief from the Black Death tunnel from 14th-century England to 20th-century New Zealand.

- Actors

- Bruce Lyons, Chris Haywood, Marshall Napier, Hamish McFarlane, Paul Livingston, Jay Laga’aia, Noal Appleby, Sarah Peirse

- Release date

- March 3, 1989

- Duration

- 93 minutes

- Director

- Vincent Ward

- Studio

- Home Cinema Group

What is “The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey” about?

The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey tells the story of a ragtag group of Cumbrian villagers in mid-14th-century England, who are desperate to escape the onslaught of the Black Death. With nowhere else to turn, the villagers rely on the visions of Griffin (Hamish McFarlane), a boy who is gifted with “second sight.” According to the images in his head, they must undergo a mission to place a copper cross on top of a cathedral on the other side of the world. With the blessing of a returned Connor (Bruce Lyons), one of the village chiefs, they set out on a journey to a deep cavern. With immense courage and fine copper ore in their bags, they successfully make it through the rocks and find themselves in modern New Zealand. It seems that the cave they have passed through is not just a path to a faraway land, but a portal that distorts the structure of the space-time continuum.

Connor and Griffin’s groups are separated by circumstances resulting from their shock and confusion at this strange world. Griffin and his companions head to a seized smelter, where they convince the workers to mold their copper ore into a cross, while Connor eventually disappears, chasing one of his fleeing members. After a series of comical misadventures due to their inability to understand the technologies of the modern world, they finally converge on the cathedral, and Griffin succeeds in placing the cross atop the church steeple. Suddenly, the spectators are surprised by a plot twist.: IIt was just a vision of Griffin’s, and they were still in the middle of the tunnel, struggling to get through it. When someone on the other side announces that the plague has managed to avoid them, they go back up, only to find that Griffin has been infected by the plague.

“The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey” and its approach to time travel

Time travel is a staple of the science fiction genre, not least because it opens up new dimensions of storytelling, creating narratives that would not be possible in the “natural” way we perceive them. Fraser Sherman In From now to now, we travel through time: visiting the past and the future in cinema and television Note that there are certain conventions regarding its use in fiction. Often, time travel films traverse the space-time continuum in a straightforward manner. Characters go back in time and attempt to fix things in a last-ditch effort to avert a major crisis. They may revolve around notions of causality (changing or maintaining outcomes in the manner of Back to the future), logic (contradictions and paradoxes, a bit like in Men in Black 3), and/or morality (distorting history for the greater good, as in Terminator 2: Judgment Day).

Related

The History of Francis Ford Coppola’s Very Good (and Very Bad) Time Travel and Fantasy Films

The director of “Megalopolis” and “The Godfather” transcends space and time.

Which makes The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey The film breaks away from these conventions by managing to combine these three ideas while bringing something new to the table: time travel doesn’t exactly take place in the physical world. Rather, it manifests itself in the vision of its main character, stylistically separated by its creative use of color. The present time—or in the film’s case, the medieval era—is in black and white, while visions that refer to the future are in bright colors. It’s about more than just an aesthetic choiceas the film’s most important sequence – the moment when the audience realizes it’s all just a vision – is a striking demonstration. As Griffin successfully reaches the top of the tower, signaling the success of his mission, the footage reverts to monochrome black and white, with all of the targets sitting in the middle of the cave.

This immediate return to the absence of color is heartbreaking for its viewers, suggestive of its cruel intentions. It is a reflexive recursion of massive proportions, which may be interpretive of Ward’s message that this is all a fantasy, like time travel in real life. They may have traveled through space and time, but the truth is that The Black Death is coming and there is no way to stop it. The film managed to subvert audience expectations and genre tropes by completely ignoring anything about the possibility of time travel. In a way, the film uses time travel to deny its existence. Interestingly, the only thing that comes true in Griffin’s visions is that he is the one who is going to die. After all, in the film’s denouement, he saw himself falling from the high ivory tower, hammering home the futility of this fantastic enterprise.

Social and religious nuances of “The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey”

One of the most complex things about The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey it’s about his social and religious questions of the Middle Ages. Ward himself notes that the idea for the film came from a conversation he overheard while traveling in Ecuador. According to the filmmaker himself, a man was describing a dream in which a city made of iron and glass shimmered and glowed across the cosmos. Ward then imagined If a poor young man were to experience this visionWould he have had the same thoughts? This is evident in the very nature of the characters themselves. The Cumbrian villagers are poor, desperate to escape something that would wipe out their entire population. At such a time, they can only rely on their faith to secure their salvation. The journey they undertake is reminiscent of a pilgrimage, a long and arduous journey to the holy land that holds their answers – the final destination being a cathedral, an obvious reminder of this. The combination of these two factors immerses the audience in their dire situation. One can quickly imagine the fear and paranoia that enveloped people in the Middle Ages when faced with such a deadly disease.and the despair of salvation.

In essence, Vincent Ward’s time manipulation film is a cinematic achievement that takes the idea of time travel to a whole new level. While it may not be as thrilling as other science fiction or fantasy stories, The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey sometimes has a rhythm similar to that of molasses – It bridges the gap between the fantastical world of science fiction and the heartbreaking indifference of reality.

The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey is currently available to stream on Arrow Player in the United States

WATCH ON ARROW