With so many distribution, streaming, promotion and marketing options and expectations, the business of being an established artist has become a very heavy burden for artists and their managers. That’s one reason why Mick Management partners Jonathan Eshak said, “We don’t want to call ourselves a management company anymore. We’re a music company. What we do more than anything is brand development, artist development — world building… We’re not just trying to keep the train on the tracks.”

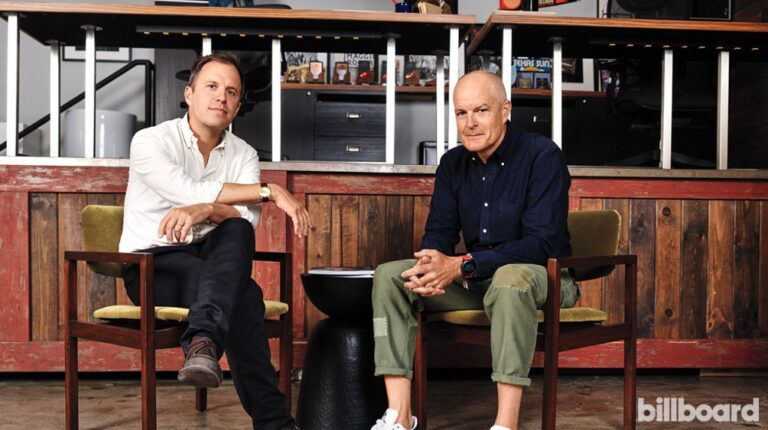

Eshak and his colleagues, Michael McDonaldfounder of the company, entered management after immersing himself in other business sectors. McDonald served as tour manager for the Dave Matthews Band before co-founding ATO Records in 2000 with Matthews; his manager, the founder of Red Light Capshaw Castings; And Chris Tetzeliwho later founded 7S Management. He opened Mick’s the following year with John Mayer as one of his first clients and, in 2004, brought in data scientist Eshak, who had worked at Universal Music Publishing Group (and is the twin brother of Island Records’ co-CEO) Justin Eshak). Jonathan became a partner in 2015.

With a staff of about 20 people in New York, Los Angeles and Nashville, the duo has built a boutique firm — with its own record label, Mick Music, distributed by Believe — that represents Maggie Rogers, who released the album Do not forget me in April; Leon Bridges and Ray LaMontagne, who will both release albums later this year; The Walkmen and the solo career of their singer, Hamilton Leithauser; Sharon Van Etten; Brett Dennen; Mandy Moore; My Morning Jacket; and The Marias.

In a fragmented culture where “it’s really hard to find a moment of relaxation,” Eshak says, Mick’s team excels at building a fan base committed to a roster of individualistic artists who push the boundaries of their abilities. “Every artist defines success differently, and we understand that,” he adds. “We understand that there’s no one way to do it anymore.” Their particular approach has yielded some notable recent successes. In August, Rogers will embark on an international arena tour—including two shows at Madison Square Garden—even though he has yet to reach platinum sales with an album. In 2018, Leithauser began a five-night residency at New York’s swanky, 100-capacity Café Carlyle, playing to “some hardcore Walkmen fans and some pretty confused business travelers,” as Eshak puts it. This year, Leithauser sold out 12 nights, and the concept will expand with potential high-profile guests in 2025. And in June, The Marias celebrated the release of their new album, Submarinewith a secret pop-up event in downtown Los Angeles for about 5,000 fans. Eshak said 38,000 people have confirmed their attendance.

“Each of these things shows us that we’re finding interesting ways that artists are honoring and serving their fan base,” McDonald said.

Eshak saw his first concert in the late 1980s when George Strait and his band headlined the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo at the Houston Astrodome. “Over thirty years later, I was presented with this belt buckle by the rodeo when Leon Bridges headlined,” he said. “It was just a perfect moment.”

Michael Buckner

What are the challenges of running an artist management company today compared to 25 years ago?

Jonathan Eshak: When I first started working with Michael, the recorded music business was starting to collapse. This was the beginning of file sharing companies like Napster and Kazaa. Joining Michael was interesting for that reason. He came from building a unique world, not just of the ebb and flow of recorded music success, but also, how do you do things well in terms of touring, marketing, etc. He understood culture creation, having worked with Dave Matthews and Coran.

Like the Grateful Dead, Matthews built a culture around his music.

Eshak: The Dead were the pioneers, and Mick’s ethos effectively started there. While the challenges of the industry have evolved, the code for building an artist’s career has remained the same. That is, how do you focus on building a meaningful, lasting relationship with your fan base? We always say, “How do we make the artist the most popular and not just the song?” The music is just part of the cocktail. Beyond that, how do we create a dynamic of connectivity between the artist and the fan? How do we market to them? How do we create a meaningful live show that thrives? There’s been a lot of talk about artist development throughout the history of recorded music.

Michael McDonald: Back then, there were fewer breakthrough moments, whereas now, because of technological and cultural developments, everything has been democratized. The upside is that more people can succeed. The downside is that there are fewer channels to create these breakthrough moments.

Eshak received a copy of the recording of Saturday Night Live on November 3, 2018, when Rogers appeared as the musical guest. “It’s an honor every time our artists get invited,” he said.

Michael Buckner

Maggie Rogers seems to be a prime example of someone who grew through connectivity with her fans.

Eshak: Maggie has understood the importance of connectivity from the beginning. She had a Pharrell-ity moment, for lack of a better word, and instead of sitting back and grinding, she understood the importance of traveling the world and connecting with her fans directly. To your point, she played two nights at Madison Square Garden without a platinum record. Now, she obviously wants that and we want that for her, but the people who were there are still going to be there. Even as she gets older, the number one thing on the checklist is, what are we doing for that audience?

What are some examples?

Eshak: When we announced the fall arena tour, we created pop-up stores in all the markets where people could line up to buy exclusive merchandise and, most importantly, tickets at a discount. He heard from fans who were nervous about ticket prices, so we tried to come up with a solution. Fans could walk in [into the pop-ups]point to the seating map and get tickets that are cheaper than if they paid online. Therefore, his fans understand that he sees them.

What questions do you ask before signing an artist?

McDonald: The most important thing is, “Do we love the music? Do we feel like we can really make this a career?” And then, “Are they, are they willing to put in the work?” We couldn’t want that more than they do. Part of it is research that you can do before you meet an artist. A lot of it is through conversation, but there’s also data that’s important. We’ve had great success following our passion and our guts, but it would be foolish not to use the tools at our disposal to help make those decisions. Data is Jonathan’s greatest strength and that’s why we’ve evolved to use it to inform decisions but never to make them in a hard way. If we did, we would never have signed some of the artists that we have.

Why did you partner with Firebird?

McDonald: Firebird gives us resources that companies our size don’t have. There’s a data department and an analytics department of 10 to 15 people. There’s a finance department. There’s a variety of things that allow us to leverage data and free us up to focus on our artists.

McDonald celebrated “my 50th birthday, 20 years sober, raised almost $500,000 for MusiCares and crossed something off my bucket list” by participating in the 2019 Iron Man World Championship. “It was an epic ride and one of the greatest days of my life,” he said.

Michael Buckner

What is your offer to the artists you want to sign?

Eshak: The whole point is to have a shared code, so it’s important for us to take the time to sit down with the artists and ask, “What are your goals in life besides being successful in recorded music?” It’s a very deep relationship so we talk all the time. We talk on the weekends. We’re with them at very important stages of their lives, and it’s really important for us to have at least a set of shared goals because it demands a lot from each person. Where we do a good job is acting almost like coaches now. Our job is to take a huge amount of information about how people achieve success, distill it and apply it to the artists that we represent, which are all very different. In other words, how can we do this with you so that you stay true to yourself? We can’t do that for a thousand artists. That’s not the business model that Michael and I have chosen to build.

You have a label.

Eshak: We have a label, and we work with a few artists whose repertoire comes back to them and they need a mechanism to release music. Part of that is also identifying artists that we like and helping them get their music out into the world.

Do you encourage your artists to own their master works?

McDonald: One hundred percent, if possible. Right now, we would be hard-pressed to pursue a deal that starts with timeless music that’s somewhere else. There’s always a chance that it could happen, and ultimately, it’s the artist’s decision. If they feel like this is their opportunity and they’re willing to let it go — absolutely. But one of the reasons we started the label was to say, “Okay, let’s create an easy mechanism where we can control the terms of the deal. Let’s put the music out and try to build it. Then, if a good licensing option doesn’t exist right now, let’s take a year and try to build something.” Ray LaMontagne Album Problem returned to him in May after 20 years. So, it’s not always a three-year or five-year return. But 20 years ago, we were able to take a long-term view and say, “Let’s take a lower percentage today so that at least there’s the option of selling the record X years later.”

Is your deal with the artist a percentage deal or a traditional partnership?

McDonald: It varies. We have a lot of traditional deals, but every time we have a true partnership, where we share [intellectual property] with an artist, everything is clear and transparent with their respective legal teams. There are ever-evolving ways for artists to do business with companies. We welcome that as it evolves.

A friend of McDonald’s made this box for him. “It’s where I keep my most precious and memorable little notes and keepsakes from artists, family and friends.”

Michael Buckner

This story appeared in the July 20, 2024, issue of Billboard.