Amid growing concerns about so-called “deep fakes” during the election campaign, the Federal Communications Commission has proposed the first rules to require disclosure of AI-generated content in political ads, but they may not go into effect before the election.

Regulators have been slow to address this emerging technology, which allows people to impersonate others using cheap and easily available artificial intelligence tools. FCC Chair Jessica Rosenworcel said disclosure is an important, and perhaps equally important, actionable first step in regulating synthetically created content.

“We’ve spent much of the last year in Washington scratching our heads about artificial intelligence,” Rosenworcel told NBC News in an interview. “You can’t just scratch your head and marvel at it.”

The new rules, which require TV and radio ads to disclose whether they contain AI-generated content, avoid for now a debate about whether such content should be banned outright. Existing law prohibits outright deception in TV ads.

“We don’t want to be in a position to pass judgment, we just want to put the information out there so people can make their own judgments,” Rosenworcel said.

The move was inspired in part by the first deepfake in US national politics: a robocall impersonating President Joe Biden and urging voters not to vote in January’s New Hampshire primary.

“We went all in because we want to set an example,” Rosenworcel said of authorities’ swift response to deepfakes in New Hampshire.

The political consultant behind the deepfake robot calls, exposed by NBC News, is now facing a $6 million fine from the FCC and 26 criminal charges in New Hampshire state court. The U.S. Department of Justice on Monday signaled its support for a civil lawsuit brought by the League of Women Voters.

Consultant Steve Kramer claimed he created the ad simply to highlight the dangers of AI and motivate people to take action.

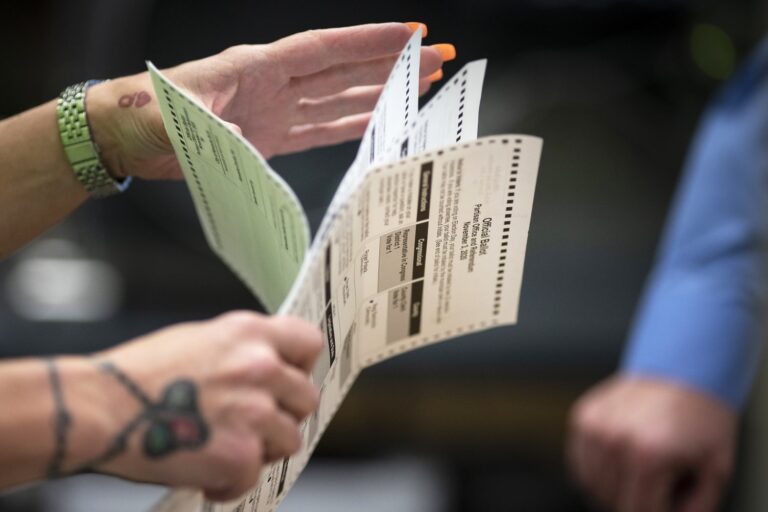

Some political ads have already started to use artificially generated content in both potentially deceptive and non-deceptive ways, and generic AI content is becoming more common in non-political consumer advertising simply because it is cheaper to produce.

Some social media companies have taken steps to ban AI-generated political ads, Congress is considering several bills, and about 20 states have passed their own laws to restrict synthetic political content, according to Public Citizen, a nonprofit that tracks such efforts.

But advocates say a national policy is needed to create a uniform framework.

Not only has social media platform X not banned AI-generated videos, but its billionaire owner Elon Musk is one of its promoters, who last weekend shared a doctored video made to look like a campaign ad for Vice President Kamala Harris with his 192 million followers.

While the government doesn’t regulate social media content, the FCC has a long history of regulating TV and radio political programming and maintains a database of political ad spending that includes information that TV and radio stations are required to collect from advertisers. The new rules simply require broadcasters to ask advertisers if their spots were produced with AI.

Meanwhile, the Federal Election Commission is considering its own AI disclosure rules, and the FEC’s Republican chairman wrote Rosenworcel, arguing that the FEC is the legitimate regulator of election advertising, and urging the commission to step down.

Rosenworcel played down the dispute between the agencies, saying the two agencies, along with the IRS and others, have played complementary roles in regulating political groups and spending for decades. The FCC also regulates a broader range of advertising than the FEC, including so-called issue ads run by nonprofit groups that don’t explicitly call for a candidate to lose an election.

Supporters also point out that the FEC is intentionally evenly split between Republicans and Democrats, making it difficult to get anything done because there is little consensus to be reached.

“We are hurtling toward an election that may be distorted or even decided by political deepfakes, a dystopia that is entirely avoidable if regulators simply require disclosure when AI is used,” said Public Citizen co-executive director Robert Weissman, who said he hopes the FCC rules are finalized and implemented “as soon as possible.”

Still, Rosenworcel said that while the FCC is moving as quickly as possible, making federal rules is a careful process that requires time to overcome many hurdles and solicit public comment.

“There will be complex issues ahead,” she said, “and now is the right time to begin this conversation.”