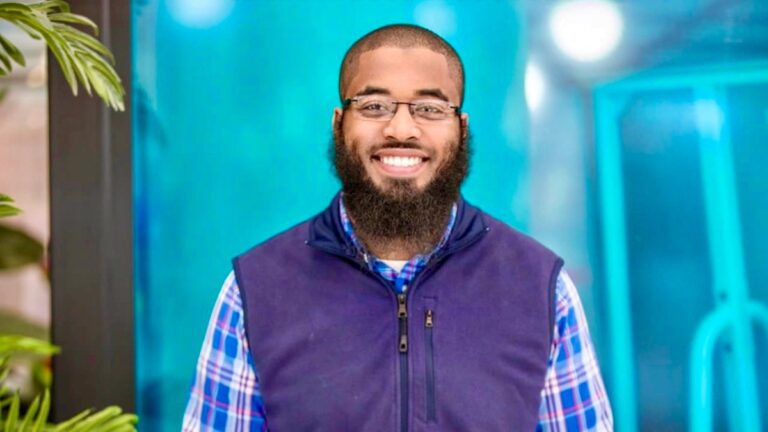

Sidney Scott has decided to retire from the venture capital rat race and is now jokingly auctioning off his vests – starting at $500,000.

Driving Forces’ solo general partner announced on LinkedIn this week that he was closing his $5 million fintech and deep tech venture fund he launched in 2020, calling the past four years “a wild ride.” Scott was backed by limited partners including entrepreneur Julian Shapiro, neuroscientist Milad Alucozai, Intel Capital’s Aravid Bharadwaj, 500 Global’s Iris Sun and UpdateAI CEO Josh Schacter.

During this time, he also helped create the first AI and deep tech investor network with Handwave, collaborating with investors from companies such as NVIDIA M12, Microsoft Venture Fund, Intel Capital and First Round Capital.

That run included about 20 investments in companies like SpaceX, OpenSea, Workstream, and Cart.com. The total portfolio generated a net internal rate of return of more than 30%, a metric that measures the annual growth rate an investment or fund will generate, Scott told TechCrunch. Thirty percent for a seed fund like this is considered solid IRR performance and exceeds the average total IRR for advanced tech, which is about 26%, according to Boston Consulting Group.

But the good performance of its first small fund was not enough.

“It wasn’t easy, but it’s the right choice for today’s market,” he wrote. Five years ago, when Scott formulated the fund’s thesis, it was a different world. Back then, most investors were eschewing hard tech and deep tech in favor of software-as-a-service and fintech, he said.

The reasons were varied. Venture capitalists tend to follow the crowd, and SaaS was seen at the time as a safe bet to make money. But venture capitalists also avoided deep tech because investors believed—perhaps rightly—that it required large amounts of capital, longer development cycles, and specialized expertise. Deep tech often involves new hardware, but it always involves building technology products around scientific advances.

“It’s quite shocking, but it’s for exactly these same reasons that many companies are now investing directly in deep tech, which is very ironic, but it’s part of the business,” Scott said. “Everyone was investing in large-scale, rapid-launch, market-entry projects. They were going to invest in these extremely smart people who would eventually turn the science project into a working company.”

He is now seeing fintech investors who would have turned him down for deals a year ago raise hundreds of millions of dollars in funds specifically targeting deep tech.

While he didn’t name names, some VCs that are heavily involved in deep tech include Alumni Ventures, which closed its fourth deep tech fund in 2023; Lux Capital, which raised a $1.15 billion deep tech fund in 2023; Playground Global, which raised over $400 million for deep tech in 2023; and Two Sigma Ventures, which raised $400 million for deep tech in 2022 (and SEC filings show that in 2024, it raised another $500 million fund).

Deep tech now accounts for about 20% of all venture capital funding, up from about 10% a decade ago. And over the past five years in particular, it has “become a destination of choice for corporate, venture, sovereign and private equity funds,” according to a recent report from the Boston Consulting Group.

With increasing competition for what are still essentially a small number of hard tech and deep tech deals, he realised this would pose a challenge for smaller funds like his.

That said, Scott also believes that many of these new entrants into the field are preparing for “a massive revelation within three years” and that the rush to invest in cutting-edge technologies has been too rapid.

When money flows into a limited number of deals, a typical venture inflation cycle begins, where venture capitalists raise the prices they are willing to pay for stakes, driving up valuations and making the industry more expensive for everyone — prohibitively so for a solo fund like his.

At a time when major exits for startups have been limited — due to the IPO market shutting down and interest in SPACs fading — deep tech has still seen successes in areas like robotics and quantum computing.

He said he wasn’t pessimistic about venture capital in general or hard tech companies, but he expected a “bullwhip effect” in deep tech investing where early-stage investors and venture capitalists would rush to repeat previous breakthroughs or high-profile successes, Scott said.

As is often the case in venture capital, he predicts that more capital will attract more investors, including those with less expertise, which he believes will lead to an increase in the number of high-tech startups. However, this could then create unrealistic expectations and significant pressure on startups to perform, he said. And, because cycles often occur in venture capital, he thinks investor sentiment could quickly turn negative if market conditions change.

“Given the extremely small number of experts and developers, as well as the capital-intensive nature of hard tech, the valuation inflation phase can be accelerated, causing startup valuations to rise rapidly,” Scott said. “This impacts the entire ecosystem, leading to funding challenges, slower development, and potential closures, which can further weaken investor confidence and create a negative feedback loop.”