(Bloomberg) — A rise in Britain’s minimum wage threatens to fuel inflation and have unintended consequences for employee benefits, putting Keir Starmer’s ambitions to boost wages on a collision course with business groups and the Bank of England.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Business groups have complained that a 10% increase in the minimum wage — also known as the national living wage — that came into effect in April is straining companies’ budgets and limiting their ability to hire. Starmer’s Labour government, which took power after a landslide victory in last week’s general election, has promised to change the lower wage threshold to reflect the “real living wage.”

Finance Minister Rachel Reeves said in her first major speech on Monday that Labor wanted to create “a more prosperous country, with more good jobs paying a living wage” and tackle the “drivers of the cost of living crisis” by pushing up pay for working families.

But business groups, labor experts and economists say continued pressure to raise the minimum wage risks fueling inflation, hurting businesses and leaving more low-wage workers unable to take advantage of programs designed to lower the costs of child care and commuting.

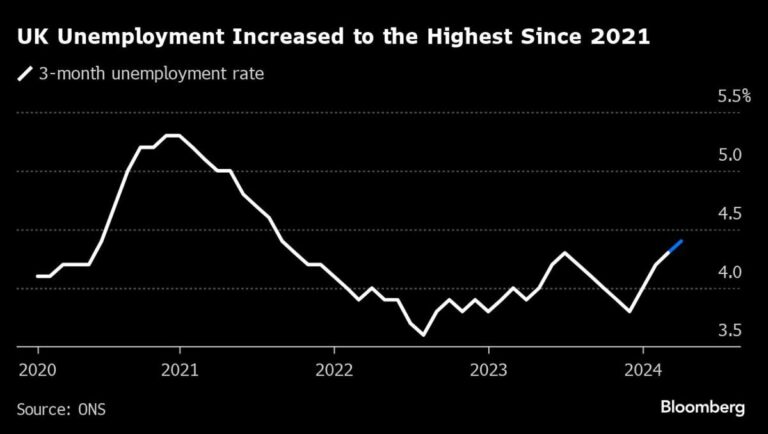

The previous Conservative government pushed for a big increase in the threshold for the lowest earners, hoping to make jobs more lucrative for those on benefits. Faster pay rises in the past two years have coincided with falling job vacancies and rising unemployment, a sign that executives may be holding off on hiring more people.

The Bank of England is watching Labour’s plans to raise wages ahead of its August meeting, when it will decide whether to lower borrowing costs from a 16-year high. The BOE warned at its June meeting that a rise in the minimum wage “could have a larger than expected impact” on wages and prices in the wider economy because the policy affects wages at higher incomes.

Policymaker Jonathan Haskel raised the issue on Monday, saying that a tight labor market would likely keep inflation above target for some time — and justify keeping interest rates on hold for now.

Regional agencies and decision-making panels “show a payroll settlement of about 5% this year,” Haskel said. That, he said, is “a sign that the matching process between vacancies and unemployment has been disrupted. Thus, each level of unemployment is associated with higher vacancies, and thus more wage pressure.”

The worry is that wage pressures will reignite inflation and make officials more reluctant to cut interest rates.

“The impact on the BOE will be limited, but with the risk of slower rate cuts if Labor delivers a sizable increase in the Living Wage,” Goldman Sachs economists said in a note, adding that the policy “may be the biggest source of risk to domestic firms with higher labor costs.”

Business leaders warn that raising the minimum wage will force them to cut jobs and raise prices, and limit their ability to raise other workers.

Currys Plc Chief Executive Alex Baldock warned the policy could make hiring more workers prohibitively expensive. The CBI, the country’s largest employers’ group, has called for a new approach to raising living standards. The British Chambers of Commerce has pointed to the limits of employers’ ability.

Labour’s pledge could be interpreted as raising the minimum wage in line with inflation or a more ambitious increase to match the real Living Wage. That could suggest the need to raise the minimum wage to 70% of the average wage — up from 66% currently, according to the Resolution Foundation.

Many employees are also unhappy. British workers can give up some of their pre-tax earnings in exchange for benefits such as extra days off, cycling arrangements, childcare vouchers or extra pension contributions, as long as their salary sacrifice does not take them below the national minimum wage. The sharp increase in the lower threshold has left more people earning at that level — and ineligible for the benefits.

“It’s unfair that lower-paid workers can’t take advantage of salary sacrifice compared to their higher-paid colleagues,” says Charles Cotton, senior rewards adviser at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. “The boss can take salary sacrifice, but the office cleaner or security guard can’t because they’re not paid enough.”

The lack of a pay rise means some staff at the National Health Service — including porters, healthcare assistants, cleaners and 999 call responders — “can no longer access the support schemes they have used for years,” said Unison, a workers’ group.

“They will now spend more money on childcare costs, season tickets and parking,” said Helga Pile, head of health at Unison.

Employers are finding it increasingly difficult to raise wages to meet the statutory requirements, leading to more jobs falling into the minimum wage category. The number of minimum wage jobs is set to reach 2 million as a result of the minimum wage increase, up 25% from 2023 and around 7% of the workforce, according to estimates from the Low Pay Commission.

“This is the second 10% increase in two years, which is a big increase for many employers,” said Stuart Hyland, reward services partner at Blick Rothenberg. “We’re now targeting people who were 20% above the minimum wage two years ago, which is a growing group.”

British car dealer Vertu Motors recently said the policy had led to a doubling of the proportion of workers paid at or within 5% of the minimum wage to almost a quarter, citing the lack of access to salary sacrifice schemes as a major source of staff dissatisfaction. Employment experts also warned that lower-level workers did not feel rewarded for their extra effort.

The problem is particularly serious in the retail and hospitality sectors, which have a large share of minimum wage workers. It also adds to inflationary pressures on wages generally, an issue the Bank of England is watching closely.

One alternative would be to provide targeted tax relief for the lowest earners, Hyland said. The opposite is true because Labour has chosen to stick with the Conservatives’ hidden tax and keep income tax rates unchanged since 2021 rather than raising them in line with inflation — meaning fewer workers will fall into the bottom income bracket each year.

“We need to get more money into the pockets of the poorest people, but many businesses are still wondering if that’s the right way to do it,” Hyland said. “It means someone has to pay for it somewhere and we know that’s just going to drive up prices.”

–With assistance from Jamie Nimmo and Andrew Atkinson.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Copyright ©2024 Bloomberg LP