Michael J. Hicks

Many economic development leaders and elected officials treat their states or cities like businesses. They approach economic development policy by trying to make their places competitive by offering tax incentives or direct subsidies. They also worry about image, trying to market their communities as if they were products or services.

This approach sounds reasonable, is easy to explain, and has been a universal failure.

Hicks:Republican areas are getting poorer while Democratic areas are getting richer

Indiana is a cheap place to hire workers (aside from the sky-high cost of health care), is conveniently located on major transportation routes, and has arguably the lowest tax burden and business regulation in the country. If Indiana were a business, we should be booming.

In contrast, our economy has lagged this country since World War II, with the last two decades offering the worst relative economic performance for this country on record.

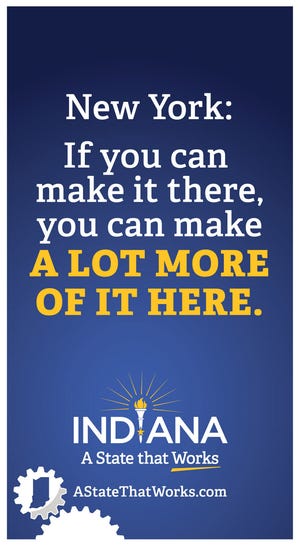

California and New York crush Indiana

To make matters worse, we also lag behind states that cable pundits often joke about, like California and New York. Both of those states have been crushing Indiana’s growth for decades. Last year alone, California grew 51% faster than Indiana, and New York grew 65% faster.

Adjusted for inflation, the average Hoosier today earns less than the average Californian in 2005 or New Yorker in 2006. This translates to a per capita income gap of more than $20,000 per year between Hoosiers and California and $11,000 between New Yorkers.

So what’s the business analogy?

Tax rates in California and New York are much higher than in Indiana, although higher health care prices offset much of that benefit. Land is more expensive in California and New York, as are construction costs. The regulatory environment for business is much more onerous in California and New York.

However, Indiana is losing a lot of its population to California and New York. For every 10 Indiana residents who move to California, six California residents move to Indiana. And, for every 10 Indiana residents who move to New York, three New York residents move to Indiana.

The ‘human capital’ effect

It’s still fun to poke fun at Californians and New Yorkers, but it’s just plain ridiculous to believe that Indiana has had an economic miracle that they haven’t. There’s something else going on, and what it is becomes very clear when you understand how economists look at economic growth.

The modern economic explanation for regional differences in growth began in the 1950s. At that time, the profession was considering differences in wealth across much of the world as we entered a period of rapid decolonization. The idea that best explained the world was one in which capital—the machinery and equipment of production—flowed from rich places to poor places in search of higher rates of return.

This idea, expressed as a mathematical model, earned Robert Solow a Nobel Prize. His theory held that, in the end, an additional truck or lathe or bridge would offer a higher rate of return in a poor region lacking capital. It was a time of genuine optimism about world poverty.

But by the late 1970s, the model’s central prediction, that poor regions would grow faster than rich regions, had failed to materialize. Instead, rich regions became richer, while poor regions tended to stagnate. Capital injections into poor countries in Africa and Asia did not produce the expected growth. It was a complex puzzle.

In the 1980s, various groups of researchers added a measure called “human capital” to the model. By human capital, they meant better education, skills, and health. In practice, the only thing we can measure to include in this equation is the educational attainment of the population.

This simple addition yields very good predictions. Today, variations of this approach explain most of the differences in living standards, worker productivity, and economic growth rates across continents, countries, states, and counties.

Education beats economic development

To put it as clearly as possible: Educational attainment alone is now a stronger predictor of a region’s economic success than all the other things combined. For developed countries like ours, there are two main elements of education that drive differences in growth.

Unsurprisingly, the first is the ability to educate the citizens of a region. Regions that successfully educate their own citizens tend to have very good economies. The reason is simple. Education tends to make workers more productive.

Of course, this is not universally true—as any faculty meeting will make abundantly clear—but on average it is. This higher individual worker productivity translates into higher starting wages and lifetime wage growth.

It is true that college graduates earn more than non-college graduates. But that is only part of the explanation.

If you’re a high school graduate, living in a city or state with a high percentage of college graduates also provides significant pay increases. Simply moving Indiana up from its current 41st place ranking to the national average for educational attainment would equate to a 5.3% salary increase for the average Hoosier high school graduate.

The reason for this observed wage increase is that less educated workers tend to be in neighborhoods with more productive workers. This also means that there are fewer less educated workers around you. This combination makes places with higher education a prime destination for people who have not graduated from college.

The second reason why education tends to benefit a region is because a strong education system is an attraction for educated people. Net migration in the US is almost exclusively from low-education areas to high-education areas.

Even the much-publicized California-to-Texas migration is dominated by people moving from lower-education areas of California to Austin, Dallas, and Houston, where 60%, 45%, and 33% of adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher, respectively. The California counties with the largest migration numbers have only 22.5% of adults with a bachelor’s degree.

The Midwest lagged the rest of the country in growth for four decades, all the while implementing economic development strategies from the 1950s and ’60s that even then showed no evidence of success. In the past few decades, nearly every Midwestern state has doubled down on those strategies, with deeply troubled projects like Foxconn in Wisconsin and the LEAP District in Indiana.

This failed business-attracting strategy is happening at the same time that we are seeing deep cuts to education, particularly higher education. If an evil Bond villain were to devise a set of policies that would ensure long-term economic decline in the developed world, it would be in two parts. First, spend huge sums on business incentives that offer a false narrative of economic vibrancy, and then slash education spending.

Welcome to the Midwest, circa 2024.

Michael J. Hicks is director of the Center for Business and Economic Research and the George and Frances Ball Distinguished Professor of Economics in the Miller College of Business at Ball State University.