The Tennessee Department of Health will hold its annual public hearing on Ballad Health’s state-sanctioned monopoly deal as the hospital faces another round of erosion in public support.

The hearing — scheduled for July 18 from 5 to 8 p.m. at Northeast State Community College in Blountville — is the last opportunity for the public to comment on the Tri-Cities area hospital monopoly created by Tennessee and Virginia lawmakers in 2018 through a law known as the Certificate of Public Benefit, or COPA.

Ballad, formed from the merger of Mountain States Health Alliance and Wellmont Health System, is a 20-hospital system headquartered in Johnson City, Tenn. It is the only hospital choice for more than 1 million residents in a 29-county region spanning Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky and North Carolina.

In the six years since lawmakers bypassed antitrust laws to allow the hospital system to exist, emergency room wait times for patients sick enough to be hospitalized have more than tripled and now far exceed benchmarks set by state officials, according to a KFF News investigation published last year into the dangers of hospital monopolies.

These Appalachian hospitals made big promises to get a monopoly. They can’t keep them.

The investigation also found that Ballad had failed to meet 80% of goals to improve quality of care and had yet to fulfill nearly $148 million in charitable obligations agreed to under the COPA agreement with legislators.

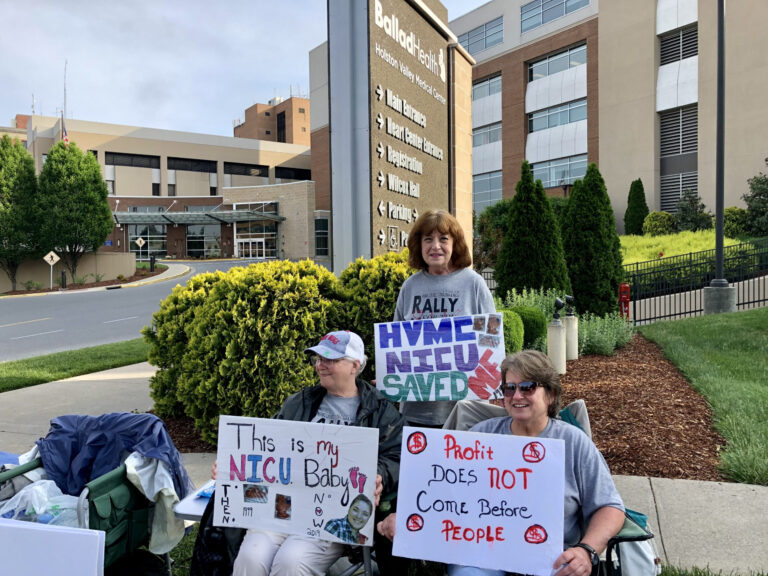

As emergency turnaround times and quality of care have deteriorated, Ballad has also closed, reduced or eliminated many emergency, intensive care and other health care services at several of the hospitals it operates, while it is trying to consolidate services in its flagship establishment.

“This is a symptom of the poor choices that Ballad Health and its CEO, Alan Levine, have made,” said Rep. David Hawk, a Greeneville Republican and frequent critic of the hospital.

“After these hearings, they never accept that they have to do better,” Hawk added. “Ballad is basically run with very few checks and balances.”

When Ballad was created, company executives sold it to the public in order to prevent hospital closures and maintain local control over the system. But over the years, the hospital closed many facilities while increasing revenue, profits and compensation for employees like Levine.

Ballad Health had a combined profit of $206 million in 2021 and 2022, according to an independent analysis by S&P Global Ratings. Levine earned $4.3 million in the final year, according to the hospital, doubling his salary as head of Mountain States Health Alliance before the merger.

The consolidation of hospital services is not unique to Ballad. A similar situation is occurring in rural West Tennessee, as rural nonprofit hospital systems believe the best way for them to remain financially viable is through consolidations and service reductions.

Ballad officials said the merger likely prevented more closures and kept a for-profit hospital system from entering the market, further degrading health care services.

Ballad’s political connections

Levine has close ties to top Republican politicians in several states. He served on the health care transition teams of Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, Rick Scott and Jeb Bush.

Gov. Bill Lee appointed Levine to the Tennessee Charter School Commission. Since 2018, Levine, his wife and Ballad’s political action committee have donated $85,500 to Lee and his inaugural fund.

But Ballad’s initial approval predates Lee.

State Sen. Rusty Crowe, a Republican from Johnson City, sponsored and helped advance the COPA agreement through the Tennessee General Assembly as chairman of the Senate Health and Welfare Committee.

At the same time, Crowe was a contractor for Mountain States Health Alliance and continued to report Ballad Health as a source of income on his disclosure statement. Tennessee law does not require public officials to report the amount of income received.

Overall, COPAs are rare, with only 10 in existence, according to information gathered by The Source on Healthcare Price & Competition, a website of the University of California College of the Law-San Francisco.

In Tennessee, Ballad’s deal has created a vacuum as officials at the Department of Health and the attorney general’s office fail to agree on who regulates the hospital system.

When asked who enforces the obligations of the COPA agreement, Tennessee Department of Health spokesperson Dean Flener told KFF News it is the responsibility of the attorney general’s office. But Amy Wilhite, a spokeswoman for the AG’s office, provided the news agency with documents indicating that it was the responsibility of the Department of Health.

The Lookout reached out to a spokesperson for the Department of Health but had not received a response by the time of publication. A spokesperson for Ballad Health declined an interview request.

GET MORNING HEADLINES IN YOUR INBOX