By Twumasi Duah-Mensah

Every so often, Megan Conner, a nurse anesthetist in Greenville said she sees a patient who’s driven for hours to come for a screening colonoscopy but who instead has to be sent to the emergency department.

“I’m looking at their blood pressure on the monitor, and it’s super high, like, 200 over something,” Conner said.

She asks her usual questions: Have they had high blood pressure before? No. High cholesterol? No. Ever had a heart attack? No.

Do they see the doctor regularly? No.

It frustrates Conner that so many patients, who have to travel sometimes hours for care in eastern North Carolina, end up not getting it because of common ailments they can’t get treated closer to home.

That’s why Conner is a big believer in the Safe, Accessible, Value-directed and Excellent Health Care Act (SAVE Act), which would give advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) like her full practice authority. She argues the data show that more nurse practitioners would provide primary care in rural North Carolina if the state would give them autonomy to practice, bringing care to small burgs that often go without.

And now, the demands for care are being driven by hundreds of thousands of patients newly eligible for care because of Medicaid expansion. Along with a growing number of lawmakers who believe the legislation is overdue, advanced practice nurses thought this would be the year that the SAVE Act finally passed.

They were wrong.

Trojan horse

Bills like the SAVE Act — to broaden APRNs’ scope of practice — are not new. In fact, efforts go back decades.

The SAVE Act, was filed early in the legislative biennium that started in February 2023 in both the North Carolina House of Representatives (HB 218) and in the state Senate (SB 175), and the number of cosponsors between the two chambers quickly grew to 79 lawmakers.

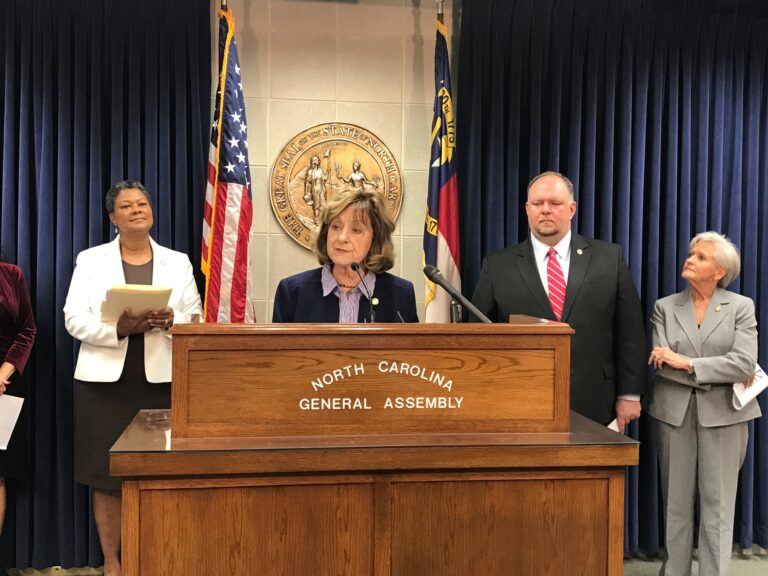

“I don’t know if we’ve ever had a bill with that many cosponsors,” said Sen. Joyce Krawiec (R-Kernersville) who has served in the legislature since 2012.

Although neither bill went far, the idea resonated throughout the legislative process. Language from the SAVE Act made an appearance in a version of the 2023 Senate budget that passed in that chamber and was part of negotiations with the House.

In the end, SAVE Act language was carved out of the final budget.

At the beginning of the 2024 session SAVE Act champions were encouraged when the bill’s language was rolled into a different bill, HB 681, which would streamline the process for out-of-state physicians to get licensure in North Carolina.

When the Senate Health Care Committee met in May to discuss HB 681, it took about five minutes to discuss the part about medical licensure.

The second part — with SAVE Act language — was new, and questions about it took up the rest of the hour. One new addition was that the bill proposed a limit on how many surgeries an anesthesiologist could supervise; currently, anesthesiologists can monitor up to four surgeries at a time that a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) is administering.

At the same time, the revised bill gave full practice authority to nurse practitioners.

The committee met again the following week to vote on HB 681. Again, the committee found new language in the bill that would have cost anesthesiologists money by setting tighter standards on how they function.

Sen. Jim Burgin (R-Angier), the proponent of the amended HB 681, said the point of the new language was to alert lawmakers to a possible violation of federal law. He also asserted anesthesiologists have not come to the table about the SAVE Act, a bill many anesthesiologists’ groups oppose.

“They think that they don’t have to come talk to us and they can stop any legislation that happens that affects them,” Burgin said. “And I just think that it’s finally starting to dawn on people that [the anesthesiologists have] not been doing what they’re telling everybody they’re doing.”

HB 681 finally passed through the Senate Health Care Committee with no “no” votes, even as some senators raised concerns about rushing the bill through to the Senate floor. Right before the vote, Sen. Mike Woodard (D-Durham) said the SAVE Act never gets enough discussion because it’s always introduced in a short session.

“If this was the first time that we had discussed a lot of these issues, it would be one thing,” Burgin retorted. “But six years of talking about things — if this was a business, it would not be very successful because the decisions are hard to get made.”

Kimberly Gordon, a nurse anesthetist and government relations director at the North Carolina Association of Nurse Anesthetists (NCANA), said she could understand why lawmakers would not want to chew on a complex bill like the SAVE Act in a short session. That was especially understandable this year, with the budget debate centering on private school vouchers, teacher pay, medical cannabis and even the size of the budget.

A legislative leader on the SAVE Act agreed. “Unsuccessful budget negotiations sapped the energy needed to address several important bills,” said Sen. Gale Adcock (D-Cary), a nurse practitioner with decades of experience. She’s been introducing the bill since 2015 and slowly building support for it.

“To me, it really didn’t feel like we had much of a chance given that they were trying to get done by the end of June that this would be something that was taken up,” Gordon said.

Sticking together – at what cost?

In North Carolina, nursing advocates have sought legislation that would grant all four APRN groups – nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives and clinical nurse specialists – the ability to practice independently. That would allow the advanced practice nurses to run their own businesses and clinics without a physician signing off on it.

Advanced practice nurses have bridled at the fact that physicians supervise their work in name only. For a generation, “supervision” has not meant that doctors are standing by watching them work. Instead, supervision often means a meeting every few months to review a handful of cases and to hand over a check to ensure the physician continues in a contract that allows the APRN to keep working.

The nurses have argued that they’d still collaborate with physician colleagues, as needed. But they would not be financially tied to them.

Currently, only nurse midwives have that independence, as last year’s abortion bill dropped the requirement for nurse midwives to work under physician supervision after several years of initial practice.

In some states, the different advanced practice nurse groups have each sought their independence separately. For example, New York state gave nurse practitioners their independence on April 1, 2022, while the nurse anesthetists are still agitating for formal recognition.

Gordon said no North Carolina statute recognizes APRNs, so each APRN group must write its own regulations on how they practice. Gordon said a bill recognizing all four APRN groups would standardize regulation.

“It’s got to be confusing if I have to look 12 different places – I’m exaggerating, but only slightly – for what nurse practitioners can do and can’t do,” Gordon said.

Gordon admitted getting all four APRN groups full practice authority is a “heavier lift” and is a different approach than in other states. In Florida, for example, bills that give one APRN group full practice authority at a time made more progress than bills granting authority to all four APRN groups.

But Gordon said sticking together brings strength in numbers and allows the coalition to communicate how each branch of APRN practice improves with the SAVE Act.

Twenty-eight states have recognized the full practice authority of nurse practitioners, 27 recognize nurse anesthetists, 24 recognize clinical nurse specialists, and 31 recognize nurse midwives. APRNs in seven states and Guam have gained full authority all at once (though Massachusetts only recognizes the full practice authority of psychiatric-mental health clinical nurse specialists).

Skepticism and opposition remain

Lawmakers and advocates cited Medicaid expansion as increasing the need for health care providers even as there exists a shortage of providers. This is especially true in the realm of primary care where nurse practitioners are common.

“OK, we expanded Medicaid, and we throw [patients] a life vest,” Conner said. But without enough practitioners that lifeline is essentially meaningless, she argued.

On top of that, they also point to how APRNs temporarily received full practice authority during the pandemic when the attitude was “all hands on deck.”

“No big complaints to the Board of Nursing,” Adcock said. “I mean, nothing bad happened. We had a 32-month trial. That’s almost three years.”

Adcock said when she joined the General Assembly in 2014, she had to educate colleagues on what a nurse practitioner was. Now, there are fewer members to debrief, in part because even lay people have seen an APRN in a health care setting more than they did 10 years ago.

Still, skepticism and opposition remained among legislators. When asked in May about the SAVE Act’s growing momentum in both chambers, Rep. Timothy Reeder (R-Greenville) said “I don’t know that to be true.”

Dr. Karen Slocum, president of the North Carolina Society of Anesthesiologists (NCSA), said in a statement, that her group “supports maintaining the team-based model of providing anesthesia care that has a proven track record of protecting North Carolina patients.”

Adcock argued that physicians’ groups have changed their reasoning for opposing the SAVE Act from concerns about patient safety, to preserving a team-based care model. Reeder, a family physician, said many of the studies showing no difference in patient outcomes when treated by a physician or APRN were done when APRNs did not have full practice authority and are not reflective of new research.

However, studies in journals such as Health Affairs, Journal for Healthcare Quality and Medical Care examined APRNs’ complication rates in states that had expanded their scope of practice. The studies found no evidence of increased complication rates, though the latest of these studies was published in December 2016.

Certain research, including 2015 and 2019 studies in the journal Nursing Economics, a 2018 study in Healthcare and a 2019 study in Medical Care, suggests that increasing CRNAs’ scope of practice increases provider presence in rural and lower-income areas.

And then, there’s the money

One roadblock the advanced practice nurses have run smack into in their attempts at more autonomy is a wall of money given by medical groups to lawmakers. In the current election cycle, the North Carolina Association of Nurse Anesthetists PAC has given $108,100 to lawmakers and candidates as of June 30.

That pales in comparison to anesthesiologist groups, who have given $292,300 through June. Of the $319,481.28 raised by physicians’ groups, anesthesiologist groups have raised over 91 percent of it.

In addition to that, state and national anesthesiologist groups gave $120,000 in “dark money” to North Carolina Citizens for Patient Safety, a super PAC, which requires less disclosure, according to a new database published by ProPublica. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) gave $40,000 to the organization, while the NCSA put $80,000 into the fund. In some anesthesiology practice groups, members give monthly donations to their PACs and super PACs.

“North Carolina’s physician anesthesiologists have a long history of supporting candidates in both parties who are committed to policies that protect patient safety,” Slocum, the NCSA president, said in a statement.

And that support can be substantial. In just one physician group — Piedmont Triad Anesthesia — more than two dozen physicians made monthly donations of $200 to its own super PAC.

Donations given to lawmakers from physicians and physician groups in the most recent election cycle.

Donations given to lawmakers from advanced practice nurses and nursing groups in the most recent election cycle.

Of the $292,300 in regular campaign donations from anesthesiologists, $39,500 has gone to House Speaker Rep. Tim Moore alone.

Moore (R-Kings Mountain) has a major role in determining the path the bill must take in his chamber. Attempts to get a comment from Moore on whether he would bring the SAVE Act to the floor House were unsuccessful.

Adcock said that monied opposition has always been there, but it has not prevented the support for the bill from growing. She and Gordon both say lawmakers are usually willing to have a conversation about the bill, especially once they present their clinicians’ perspectives and experiences.

Both women argue that eventually, no amount of money will deny the necessity of the SAVE Act.

“At some point we’re going to reach a critical mass where this really just has to be done or people are literally going to start dying,” Gordon said.

Serving rural communities

After one of the Senate Health Care Committee meetings, state Sen. Sydney Batch (D-Raleigh) argued that some studies suggest that recognizing full practice authority does not necessarily encourage advanced practice nurses to set up practices in rural parts of the country, one of the APRNs’ justifications for expanding their role.

“I question if the motive is to go ahead and increase access to care, especially in rural North Carolina, why would we not put some triggers in there to actually encourage nurses and other CRNAs to practice in rural North Carolina?” Batch said.

Evidence from other states varies. When Arizona granted full practice authority to nurse practitioners in 2001, the number of nurse practitioners in rural areas increased by 70 percent.

Nursing advocates also argue that advanced practice nursing graduates leave the state due to restricted practice authority. Elena Meadows, NCANA president, said that data she has compiled show over 50 percent of people graduating from North Carolina programs have left.

Conner, the Greenville nurse anesthetist, grew up in Halifax County, a mainly rural county with a population of 48,622. She said she became passionate about becoming a nurse anesthetist because she saw how patients preferred her mom, a former nurse practitioner, at the health department over providers at a doctor’s office.

Conner said she came back to practice in a rural area because of the barriers rural North Carolinians face to receive care. Her parents drive an hour and a half to see their cardiologist. Her sister, a school nurse in Halifax County, often acts as the bridge connecting kids who don’t see the doctor regularly with primary care.

Conner said the SAVE Act would be “a start” for aiding rural health systems in North Carolina.

“Some of the stories break my heart for the things she has to do to take care of those kids in the school system,” Conner said, “when kids should be there and able to learn and not dealing with their health issues.”

NC Health News editor Rose Hoban contributed reporting to this story.