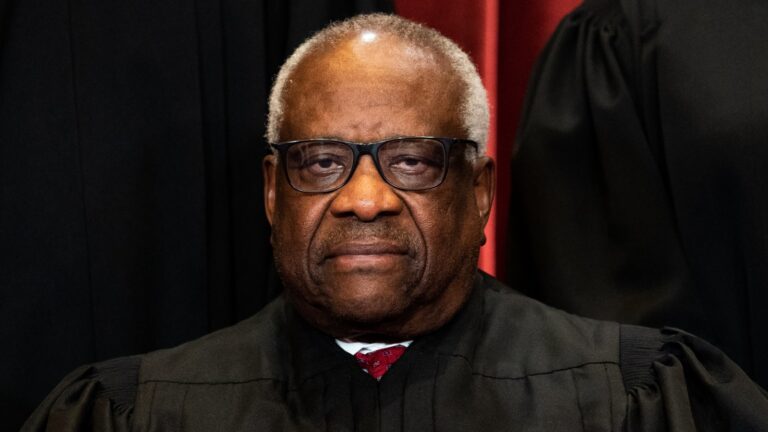

Earlier this week, Two Democratic senators have announced they are calling for a criminal investigation of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in connection with a luxury camper loan provided by a longtime executive at UnitedHealth Group, the largest health insurer in the United States.

Thomas appears to have recused himself from at least two lawsuits involving UnitedHealth while the loans were in effect. Rolling Stone Thomas chose to join another health insurance litigation on this matter, and in 2004, he authored the court’s unanimous decision, which had a broad benefit to the industry, protecting employer-based health insurers from damages when they refuse to provide certain services and patients are harmed. Thomas’ advice to patients facing such denials? Get out your checkbook.

UnitedHealth was not a party to the case, but the company was part of two industry groups that filed briefs urging the Supreme Court to side with the insurers.

“As we’ve seen so vividly this term, Supreme Court decisions can have far-reaching collateral effects. For example, when the Court rules in favor of one big insurance company, it tends to benefit all the other big insurance companies,” said Alex Aronson, executive director of the judicial reform group Court Accountability. “That’s certainly the case here, and it’s a perfect example of why judges should not accept gifts, especially secret gifts, from industry titans whose interests depend directly or indirectly on their decisions.”

At the time of the ruling, the public had no idea about Thomas’ RV loan. The New York Times Senate Democrats investigating Thomas believe most or all of the $267,230 bus loan was ultimately forgiven. Sens. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-Idaho) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) recently asked the Department of Justice to investigate whether Thomas reported the forgiven portion of the loan on his tax returns after he failed to disclose that portion in his ethics filings.

Meanwhile, employee benefits lawyer and former law professor Mark DeBofsky said Thomas’ opinions on health insurance have far-reaching, long-term implications.

“It’s still not resolved. The impacts are continuing,” DeBofsky said. Rolling Stone“People who urgently need special medical care, and [their] “Insurance companies say, ‘That treatment is not medically necessary,’ and the result is that treatment, hospitalization or services are denied, resulting in unnecessary death or serious injury that goes uncompensated, to your detriment.”

Since last year, the Supreme Court has been facing an unprecedented ethics crisis, with much of the focus on Thomas. ProPublica reported that Thomas accepted and failed to disclose lavish gifts from conservative billionaire Harlan Crow for two decades. Crow allegedly provided Thomas and his wife with free private jet and superyacht travel, bought a house from Thomas so the justice’s elderly mother could live there for free, and paid for at least two years of boarding school tuition for Thomas’ nephew.

last year, Times Another friend of Thomas’ reportedly loaned the judge money to buy a luxury RV, then later forgave most of it, which was central to the judge’s “down-to-earth” persona. 60 minutes A few years ago, a journalist from the program The judge, who rode on the bus with Thomas, reported that the judge and his wife use the vehicle to “tour the United States during vacations,” “sometimes spending the night in Walmart parking lots.”

Thomas received a $267,230 loan for the RV from health insurance executive Anthony Welters in 1999. Welters said: Times“I lent the money to a friend. I’ve lent it to other friends and family. We’ve all been on one side of that situation. He used the money to buy a camper, which is his hobby.”

At the time the loan was made, Welters was CEO of AmeriChoice, a health maintenance organization (HMO) that serves Medicaid patients. He went on to become a longtime employee at the company after it was acquired by UnitedHealth in 2002 for $530 million in stock.

UnitedHealth featured Welters on its website as one of its business leaders in 2004. Two years later, the company named Welters executive vice president at the UnitedHealth group level. The following year, the company announced that Welters would lead UnitedHealth’s public and social markets group. By 2013, Welters owned 583,506 UnitedHealth shares, worth about $36 million at the time. He retired from the company in 2016.

According to memos released by the Senate Finance Committee, Welters extended Thomas’ RV loan for 10 years in 2004. Welters forgave the loan in 2008, and Thomas wrote in the memo that he did not want to receive any more RV payments because he had already paid sufficient interest. Committee staff wrote in a review of the documents that Welters “forgave a substantial or full amount of the principal balance of the loan to Clarence Thomas.”

According to Supreme Court records, Thomas did not participate in any deliberations on two cases in which UnitedHealth was named as a party between 2002 and 2005.

Federal law requires that Supreme Court justices recuse themselves in any case “where their impartiality may be called into question.” Justices decide for themselves when such action is necessary. And when justices recuse themselves from cases, they rarely give reasons for doing so. Justice Thomas did not appear to explain why he decided to recuse himself from the two cases directly involving UnitedHealth.

Thomas did not take similar steps. Aetna Health, Inc. v. Davilaa case that had broad implications for the health insurance industry. He instead wrote the court’s opinion expanding ERISA, the tool insurers favored to limit their liability.

Congress passed the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 1974 to protect employee benefits. The act is relatively vague about what constitutes “employee benefits” and contains broad override provisions. Courts have filled the gaps. Aetna Health This case has dire consequences for patients: Half of Americans have employer-sponsored health insurance, and nearly all of these plans are regulated by ERISA.

“[If] “Whether you work for a corporation, a limited liability company, a partnership, or a sole proprietorship with employees, if your employer provides benefits, ERISA applies,” explains employee benefits attorney DeBofsky. “There’s no malpractice liability if your health plan denies you life-saving or medically necessary treatment and you incur losses as a result.”

The 2004 Supreme Court ruling Aetna Health Helping to solidify this harsh reality was the case involving two patients who separately sued Aetna and Cigna in Texas for harm caused by wrongful denials of treatment.

The first patient was prescribed a particular arthritis medication by her doctor. Aetna refused to pay for it and required the patient to try other medications first, one of which caused severe internal bleeding. After the second patient underwent a hysterectomy, Cigna discharged her after one day of hospitalization, despite her doctor’s advice. She suffered post-operative complications and was forced to be hospitalized again.

Justice Thomas authored the Court’s unanimous decision in the case, ruling that because ERISA preempts state law, patients are not entitled to damages for injuries caused by unjust medical treatment decisions, and therefore, patients are only entitled to reimbursement for the costs of services that were wrongfully denied.

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, in their concurring opinion, agreed with the Court’s decision and called it “consistent with our governing case law on ERISA’s preemptive scope.” But they also called on Congress and the Court to reconsider “what constitutes an unjust and increasingly complex ERISA regime.”

“Rather than typical medical malpractice damages – bodily injury, pain and suffering, disability, disfigurement, economic loss, etc. – the only damages the Supreme Court has found potentially allowable are the costs of increased hospital stays for patients. [patient] “Questions arose about which patients developed infections after surgery, or what it would have cost to prescribe a different drug that didn’t cause internal bleeding,” DeBofsky says. “That put the plaintiffs’ malpractice lawyers on the defensive because it wasn’t worth the lawsuit. They couldn’t get the damages that are common in malpractice lawsuits.”

George Parker Young Aetna HealthAfter the verdict, he said he stopped handling litigation on behalf of patients and doctors suing health insurance companies. “I just got out of that business,” he said. “That was 100% of the litigation that I was doing, and I finished that docket.”

Young noted that the Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous, and that if Thomas had withdrawn from the case without writing the opinion, his clients could have easily lost the case by an 8-0 vote.

“The one thing I would never say is, ‘Oh, if Justice Thomas had recused, I would have won that case.’ I can’t say that, and it would be disingenuous to say that,” he says.But looking back on the RV loan Welters provided, Young says, “It was just awful.”

“I would have filed a motion to exclude from the lawsuit” if I had known about the loans during the litigation, he said, adding, “There is no doubt that this litigation will have an impact on all HMOs nationwide that provide employer-based health care.”

UnitedHealth is Aetna Health At the time of the lawsuit, the company was a member of two industry groups that filed amicus briefs in support of Aetna and Cigna, the American Health Insurance Association (now known as AHIP) and the American Employee Benefits Council.

Mr. Thomas, through a Supreme Court spokesman, did not respond to a request for comment. Ms. Welters did not respond to a request for comment sent to her organization, the Black Ivy Group. UnitedHealth declined to comment.

Thomas’s opinion suggests that at one point, patients whose claims were denied by Aetna and Cigna should have paid out of pocket for needed services and drugs.

“If benefits were denied, defendants could have paid for the treatment themselves and then sought reimbursement or sought a preliminary injunction,” Thomas wrote.

Young denies the allegations. “That’s not true. My parents didn’t have those assets,” he says, noting that one of his patients was a manual laborer and the other had just given birth and needed to stay in the hospital for a few extra days. “The costs are not small, and it’s not like they had any credit left to pay the medical bills.”

Not everyone needs to think that way, Young points out: “In Justice Thomas’ world, if you need to pay your medical bills, you can just ask Harlan Crow.”