Of all the courses offered by the Della Keats Pre-College Program, the three high school seniors in the hall at the University of Alaska Anchorage were particularly impressed by the cadaver lab in their anatomy and physiology class. It’s not the kind of opportunity students in rural Alaska usually get, and that’s the problem.

Bristol Albrant, a 16-year-old from Ketchikan, said the experience was indescribable. “It’s really not normal. People just don’t get the chance to have donors like that,” she said.

For Tanya Nelson of Napakiak, it was the first time she had seen a dead body. “It was probably the first time for most of us,” she said with a smile.

Albrant wants to go to medical school, Nelson is interested in a career in nursing and Cruz Kvaznikoff, an 18-year-old from Nanwalek, said his interest in becoming an EMT was sparked by his father, who works in the medical field.

All three are living in Anchorage for a month as part of a program aimed at promoting early college success for rural Alaska Native students or other underrepresented groups interested in health-related careers. The program is named after Della Keats, a traditional Inupiaq healer from the Noatak region.

The Della Keats program was shut down for six years due to a lack of funding, but it is back for the first time since 2018. Halfway through the program, its organizers learned that the initiative had won a $1.3 million grant from the Indian Health Service that should allow it to operate for at least five more years.

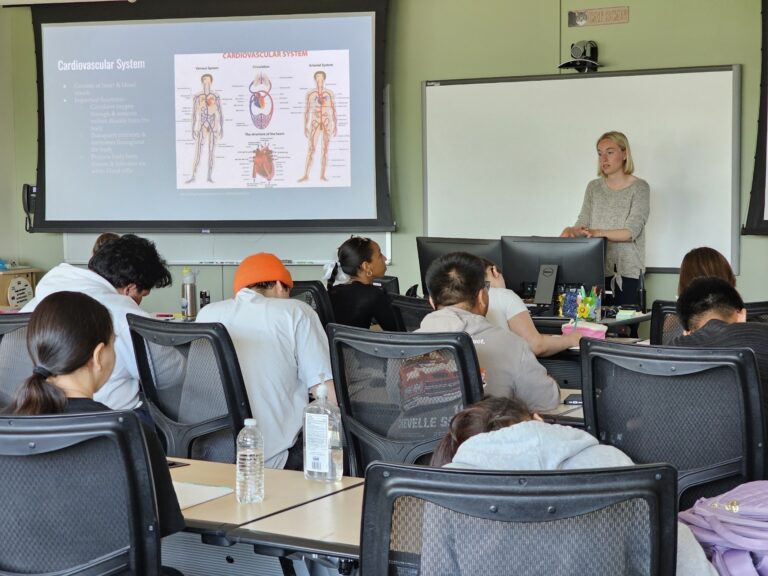

The program aims to address a health equity gap. Data shows that nationally and in Alaska, Alaska Natives and American Indians are underrepresented in health care careers. The program is aimed at students considering careers in research, medicine or health-related professions, so Alaskans benefit from a more diverse health care workforce. The restart of Della Keats comes as the state grapples with a significant nursing shortage as a result of the pandemic.

Gloria Burnett, director of the UAA’s Alaska Rural Health and Workforce Center, said several previous grant applications had been unsuccessful, so this news comes as a relief. She added that it eases the burden of addressing financial issues so administrators can focus on getting the program up and running.

“A lot of these students don’t have access to these types of opportunities in their home communities, so there’s a culture shock of going from their small home community to a bigger place like a university,” Burnett said. “We’re trying to make it a more comfortable place and space for them while they’re still in high school, so they can graduate more easily.”

Burnett said the new funding means they will add new elements to Della Keats, including outreach to students in grades K-8 and the creation of an Alaska Native learning community for undergraduates in the University of Washington’s multistate medical education program, known as WWAMI after the initials of the participating states: Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho. The program has staff and classes on the UAA campus.

“Getting kids interested is one thing, and I think we do a great job of that in Alaska, but it doesn’t necessarily lead to higher education,” she said. She says Keats bridges that gap by showing students what the programs are like, what the requirements are, and introducing them to the paperwork and financial aid. She also shows them how to live independently. Students live in dorms and receive a stipend that they must budget for things like daily lunches and weekend activities.

Students like Albrant, Nelson and Kvaznikoff benefit from college-style classes and independent dorm living with the support of mentors who have gone through the program and are now in medical school.

Chanmi Joo, a program alumna who just completed her first year of medical school at the University of Washington, has participated in Della Keats twice. This is her fourth year as a mentor.

“The cadaver lab was also my favorite. And it not only solidified my desire to go into medicine, but I think it also helped me realize that this is how I can have an impact. Not just on patients, but on the future generation,” she said.

Joo said the program helped kickstart her journey to becoming a surgeon by helping her decide which areas of the medical field were best for her, so she wants to be part of this program for the next generation of health workers.

Nelson, who wants to return to Western Alaska to pursue a nursing career in the central city of Bethel, said the program helped her decide which areas of medicine weren’t a good fit for her either. “I’m not interested in research,” she said. “I want to see patients.”

“Yes, I’m getting involved,” Kvaznikoff added.

Albrant agrees: “I don’t like working in a lab. I prefer to understand a problem and then solve it.”

After medical school, she said she also wants to return to Alaska. “I think for school I might want to move,” she said. “But then I’ll definitely come back to Ketchikan so I can give back as much as I can.”

GET MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX