If you ask the average Indonesian voter what they think it takes to be elected as a legislative candidate, you will likely hear something like this:Hals Punya Duit“—”[they] There has to be money.”

These voters’ intuitions are supported by numerous studies showing that political campaigns in Indonesia are expensive, and the costs are on the rise. To win legislative elections, political aspirants must pay the salaries of vast campaign teams, buy loads of campaign equipment, and hand out envelopes of cash to voters on election day. These expenses can be more than $50,000 for district or city-level candidates, and for parliamentary candidates, political aspirants can spend more than $2 million. The costs are borne by individual candidates, not political parties, and failure to win can lead to financial ruin. Given the obvious advantages that personal wealth gives candidates in such a system, it is no wonder that an increasing number of businessmen and oligarchs are entering politics.

The reality of all this was on full display when Indonesia held city, district, provincial, and parliamentary elections in parallel with the presidential election in February 2024. Legislative candidates we spoke to described their campaigns as financially “grueling,” with tens of thousands of candidates spending huge sums of money, leading some to conclude that this year’s election was the most expensive in Indonesia’s democratic history.

Given the skyrocketing costs of campaigning, it’s no wonder voters think only the wealthy can run for office. how How much wealth does it take to win a seat in Indonesia? And do some candidates need more funding than others? Until now, researchers have not had the data to systematically explore the impact of parliamentary candidates’ personal wealth and campaign spending on their chances of electoral success. To fill this gap, we took advantage of the 2024 elections to conduct an original survey of candidates that allows us to test for the first time the extent to which wealth generates representation in Indonesia’s local parliaments. We also explored the extent to which funding offsets countervailing factors that are thought to reduce candidates’ chances of success. Do candidates facing “demographic headwinds” (e.g., women) need more funding to compensate for their electoral disadvantage? Conversely, do some candidates need less funding, such as those with dynastic ties and who can use their names and networks to their electoral advantage?

data

To explore these questions, we leveraged Indonesia’s first-ever panel survey of legislative candidates. Starting in November 2023, we worked with Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting to survey a random sample of candidates running for city council seats (Kota) and district (prefectureThe survey targeted the DPRD Tingkat II (PTA)-level parliament. Due to feasibility concerns, we placed some restrictions on the candidate pool, restricting the sample to candidates who are in the top three positions on the party list and running for parties with more than 1% support as of 1 October 2023. We also excluded candidates running in Papua and Maluku due to concerns about the costs associated with surveying respondents in hard-to-reach areas.

Our study was a panel study, and we attempted to survey the same 800 candidates three times: twice before the election, in November 2023 and January 2024, and once after the election, in April 2024. Ultimately, we achieved a recontact rate of 81%, with approximately 650 candidates surveyed across all three rounds. Thus, we believe these data provide a uniquely detailed portrayal of legislative candidates’ attitudes and behaviors as they change over the course of their campaigns.

Investigation result

We have established some stylized facts about the relationship between wealth and representation in Indonesia, which characterize a larger phenomenon that we plan to explore in a series of related articles using this new dataset. First, in Figure 1, we see a significant linear relationship between wealth and electoral success (the red dotted line represents the overall chance of winning, i.e., about 20%). The wealthier a candidate is, the more likely he or she is to win a seat. To make this finding concrete, compared to the poorest candidates (monthly income of less than Rp 5 million), the wealthiest candidates (monthly income of more than Rp 30 million) are more likely to win a seat. 15 times more likely to win Their Race.

Figure 1: Candidate income vs. probability of winning

In Indonesia, election campaigns are largely self-funded at the local level, so wealthy candidates spend more than poorer candidates. But what do wealthy candidates spend their money on to improve their chances of winning?

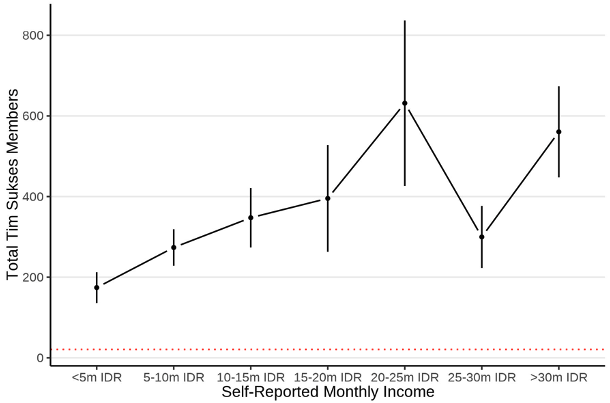

In our survey, composition Of their spending: Wealthy local candidates continue to spend big. Baliho (banners) and vote buying. In other words, it is not the case that wealthier candidates are more likely to employ different, more sophisticated election strategies. Instead, what we find is evidence that wealthier candidates are simply able to build larger election teams (Tim SachsFigure 2 plots the size of campaign teams as a function of candidates’ monthly income, and shows that wealthy candidates are able to build patronage networks three times larger than their poorer opponents.

Figure 2: Relationship between candidate income and campaign team size

These findings will likely come as no surprise to observers of Indonesian politics. However, our primary interest in this project is to understand the extent to which money influences Indonesian elections. In this regard, the significance of our findings deserves reexamination: money far outweighs other traditional predictors of success. By comparison, consider that men are only 2.5 times more likely to be elected than women, that those with a tertiary education are three times more likely to be elected than those with a high school diploma, and that the oldest candidates are only twice as likely to be elected as the youngest candidates.

In other words, the advantage enjoyed by wealthy candidates outweighs nearly every other characteristic thought to predict electoral success. We explore these results in more detail in Figures 3 and 4. Taking gender in Figure 3 as an example, wealthy men generally perform better than wealthy women. Men also tend to be wealthier than women. But wealthy women perform significantly better than poor men. For example, women who report a monthly income of more than Rp 30 million have a 42% chance of winning, which is roughly 8 times This is higher than the 5% success rate reported by men earning less than Rp 5 million a month.

Figure 3: Relationship between candidate income and probability of winning (by gender)

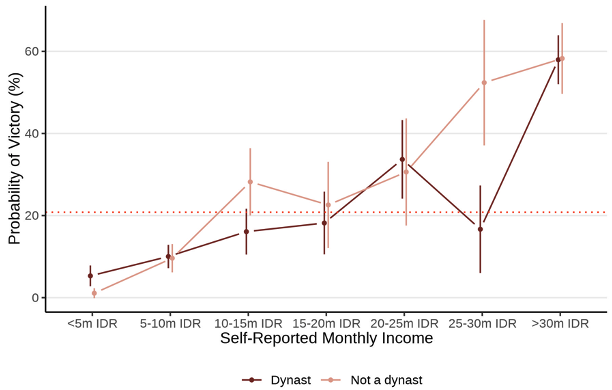

In Figure 4, we perform a similar analysis looking at the status of candidates being members of political dynasties. The election of Gibran Rakabuming Raka as Vice President with Prabowo Subianto’s endorsement has rightly sensitized analysts of Indonesian politics to the influence of nepotism in structuring electoral politics. However, Figure 4 shows that in terms of the electoral advantage of wealth, dynastic status does not actually matter. Indeed, it may be that dynastics and incumbents perform better simply because they are wealthier than their competitors and not because of any inherent advantage conferred by the political networks that come with their status. Figure 5 is consistent with this and shows that wealthy dynastics have comparable electoral prospects to wealthy non-dynastics, and this relationship holds across the income distribution.

Figure 4 – Candidate income vs. probability of winning (by dynasty)

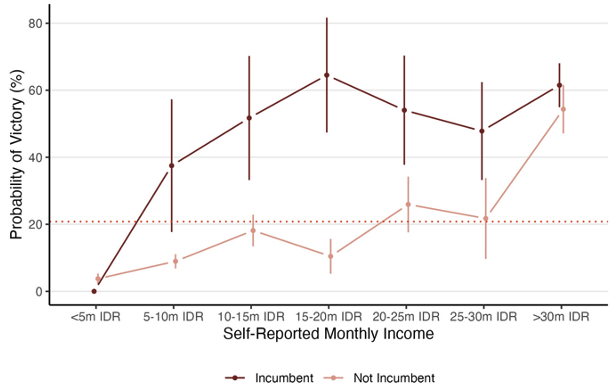

The only exception to our findings concerns the role of incumbency. Figure 5 shows that once in power, poorer candidates perform roughly as well as richer candidates, but remain at a slight electoral disadvantage. To put it in numbers, 40% of incumbent candidates earning a monthly salary of Rp 10 million won their elections, compared with 60% for incumbent candidates earning Rp 30 million or more.

The weaker relationship between wealth and victory among incumbents likely stems from their ability to leverage state resources to their electoral advantage once in office, whether they are rich or poor. Consistent with this interpretation, non-incumbents show a similar positive correlation between income and the probability of winning. However, once a non-incumbent candidate earns more than $30 million a month, their chances of winning an election become statistically indistinguishable from incumbents.

Figure 5: Relationship between candidate income and probability of winning by incumbent position

Conclusion

The survey data paint a very clear picture of the role that wealth plays in Indonesia’s parliamentary elections. We’ve known for some time that “money matters.” But the relationships between income, spending, and electoral success uncovered here are more dramatic than existing research suggests. Of particular importance, these data demonstrate the advantage that wealth confers on candidates over other characteristics often thought to play a decisive role in electoral victory, such as family ties. Arguably, over the past two decades, entrenched patterns of nepotism and underfunded political parties have driven up the costs of politics and created barriers to entry for less affluent candidates.

Related

Explaining the Prabowo landslide

Prabowo’s victory was made possible by his enduring authoritarian appeal and by the tide of battle tipped in his favour by Jokowi.

While analysts don’t know exactly how making Indonesia’s representative institutions accessible only to the super-rich will affect the quality of Indonesia’s democracy, some classic studies of political careers suggest that class has little impact on how politicians behave in power, especially in situations where party systems are strong and politicians’ actions are constrained and shaped by party ideology and policies.

On the other hand, in political systems like Indonesia’s, where policy platforms are weaker, class background may have a greater influence on how politicians behave, what they prioritize, and what policies they pursue while in office. The data presented here suggest that this is an important area of inquiry for future research, given that there is little evidence that the rise in political costs will be reversed anytime soon.