comment

[TheLabourgovernmentfrom1945to1951foughttorestoreDutchcolonialruleinIndonesia[1945年から1951年までの労働党政権は、インドネシアへのオランダの植民地支配の復活を目指して戦った。

by John Newzinger

Downloading PDF. Please wait…

Friday, July 26, 2024

problem

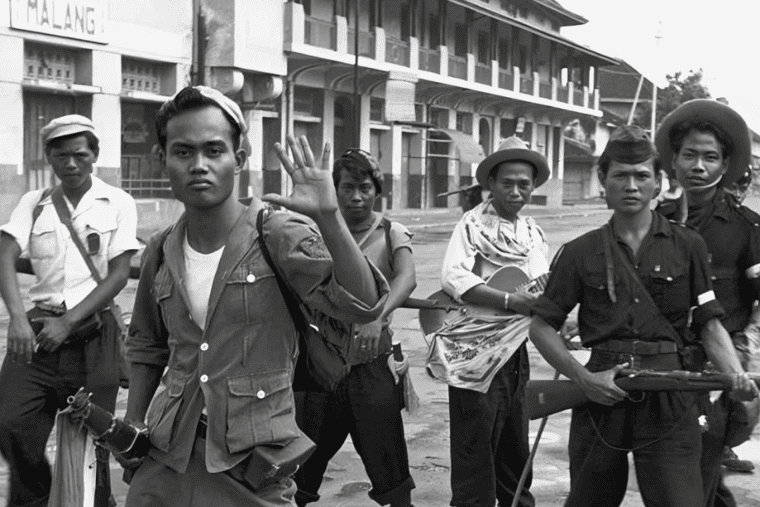

Indonesian freedom fighters, Solo, Java, 1949. (Photo: National Museum of World Culture)

[TheLabourgovernmentof1945to1951hasawhollyundeservedreputationofbeingprogressivesofarasBritishimperialismisconcerned[1945年から1951年までの労働党政権は、イギリス帝国主義に関する限り、進歩的であるという全く不当な評判を得ている。

But nothing illustrates Britain’s imperialist role more than its intervention in Indonesia in 1945-46 to restore Dutch colonial rule.

[AfterWorldWarIIendedandJapansurrenderedinAugust1945theIndonesiannationalistmovementdeclaredindependence[1945年8月に第二次世界大戦が終わり日本が降伏した後、インドネシアの民族主義運動は独立を宣言した。

It was decided that Indonesia would not be reoccupied by the Dutch colonialists who had been driven out by the Japanese. On September 19, over 200,000 people demonstrated in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, calling for independence.

Much of the country was controlled by nationalist militias. Restoration The Labour government was committed to restoring imperial rule, but not only in those British colonies that had been occupied by the Japanese.

It also played a role in the French rule of Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos, and the Dutch rule of Indonesia.

The first British troops arrived on 29 September and were greeted with nationalist demonstrations and banners in English demanding independence.

Within a very short space of time armed conflict broke out which quickly escalated into all-out war as the British attempted to crush the nationalist movement.

Ultimately, over 60,000 British and Indian troops were sent to crush the nationalists. From the beginning, the intervention was unpopular with many British soldiers.

The government was concerned that the high death toll in the process of Britain restoring Dutch colonial rule could create problems at home.

The government therefore decided to rely as much as possible on the Indian troops, whose lives were deemed less important, and to rearm the surrendered Japanese garrisons.

Fierce fighting soon broke out across Indonesia, with the battle for the port city of Surabaya proving to be the decisive battle.

Here, from late October to November, over 20,000 British troops fought against poorly armed nationalist militias, while British warships bombarded the city and British aircraft bombarded it mercilessly.

Muriel Walker, a Scottish woman who lived in the city, collaborated with the nationalists and broadcast to the British troops on a rebel radio station, urging them to stop fighting.

She was known as the “Surabaya Sue.” She described how “hundreds of people were killed,” “the streets were flooded with blood, women and children lay dead in the gutters… but the Indonesians would not surrender.”

The British drove out most of the city’s population and it was left in ruins. At least one British unit refused to fight during the war and was forced to redeploy.

Australian troops have frequently taken part in nationalist demonstrations and have sometimes provided arms to rebel groups.

In Australia, unions refused to allow troops and munitions to be sent to Indonesia, eventually resulting in over 500 ships being stopped.

To break the boycott, the British government invited the Indian maritime workers, along with the King’s brother, Prince Henry, to address them personally and praise their loyalty to the British Empire.

Boycott However, the interpreter changed the speech into an impassioned plea in support of the boycott, and all the maritime workers walked out and joined the picket line.

British soldiers aboard British warships also collected funds for the strikers, and about 600 Indian soldiers actually bore arms against the rebels.

By the time the last British troops withdrew at the end of 1946, imperialist forces had killed more than 20,000 Indonesians.

No one doubts the Clement Attlee government’s imperialistic leanings: it was written in blood.