From the day the general election was called, there was much talk that it would take place when many Scottish schools were on holiday.

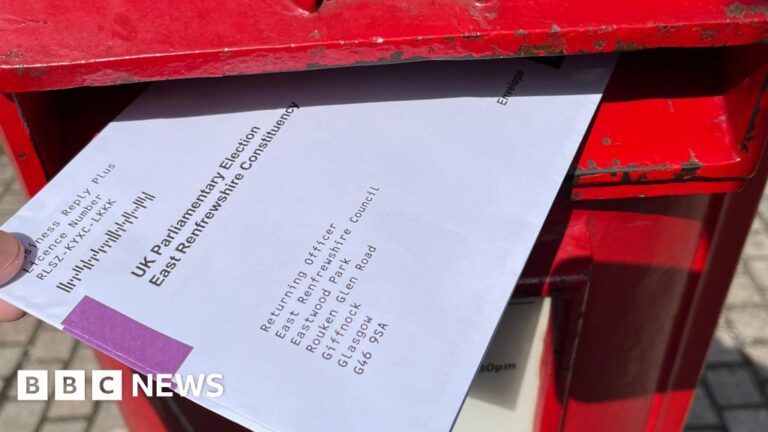

This has raised concerns about postal voting, with numerous stories of families leaving for overseas destinations before their ballots even arrived on their doormats.

Those who followed the instructions missed out on voting rights, and political parties were confident it would make a big difference with the polls so close.

But ultimately, how widespread was it? Did the overlap of voting days with school holidays actually change the outcome in some key electoral districts?

While mail-in voting has increased dramatically since COVID-19, it has actually been steadily increasing for years.

In the 2019 general election, 21% of Scots registered to vote by post; in 2024 that figure will rise to 24%, just shy of one million eligible voters.

There are significant differences across the country: in Edinburgh West a third of voters chose to vote by post, but in Coatbridge and Bellshill just 16% did so.

Edinburgh City Council had to process and send out more than 100,000 pieces of paper across five constituencies – no small task for a surprise election, and which may offer a clue as to why some papers took longer to arrive than others.

People who register to vote by mail have always been much more likely to actually register to vote, and in 2017 and 2019, about 83% of ballots issued were returned.

So can changes in mail-in voter turnout figures help us determine whether the holidays deprived a significant number of voters of the opportunity to express their views?

Let’s start with Glasgow. Boundary changes have reduced the city’s number of seats from seven to six, and constituency map boundaries have shifted all over the place, but it’s still possible to calculate the average postal ballot return rate across the city.

In 2019, it was 76.5%. This year, it’s 73.5%, down three percentage points.

That’s not a small number, but the number of voters registered to vote by post in Glasgow is low – below 20% in most constituencies – and 3% – less than a fifth of the electorate – doesn’t amount to much.

Even if we were to be bold and assume that the drop in turnout was entirely due to the holidays, and that all voters rejected by postal voters supported the SNP, that would not have prevented Labour from making a big advance.

The same is true in Edinburgh, where postal voting is much more common.

In 2019, the average return rate for mail-in ballots in the five city districts was 84.3%. This time, it was 83.2%, a drop of more than a percentage point but again not enough to affect the outcome.

So let’s look at some of Scotland’s closest constituencies, where the outcome was decided by fewer than 1,000 votes.

Dundee Central was the safest constituency before the vote but is now the closest in Scotland, with the SNP’s Chris Law defending his victory but by just 675 votes.

What about postal voting?

Boundary changes have made this more difficult again, but in 2019 the average return rate for the former Dundee East and former Dundee West constituencies was 83.8%.

In the new centre seats, which cover large swaths of the east and west, support was 79.3% – a drop of 4.5 percentage points.

If return rates remain as they are, an additional 696 ballots would have been returned, or 4.5% of the 15,472 mail-in ballots issued.

In theory that would be enough for Labour to win the seat, but almost everyone would follow the same path.

Neighbouring Arbroath and Broughty Ferry was another closely contested constituency, where the SNP won by 859 votes, but postal voter turnout across the area fell by around four percentage points.

If the return rate had held up, an additional 812 votes could have been obtained, which would have been very close to the final majority.

Elsewhere, the Conservatives retained Dumfries and Galloway with a 2% majority. Postal voting is more common here, with 28% of voters registered, but return rates fell by 5 percentage points this year.

This five-point drop equates to 1,116 votes in a seat with a majority of 930. Nearly all of the votes enough to make a difference went to the SNP.

But the picture is not particularly uniform, as can be seen in the chaos in the north-east, a close contest between the SNP and Conservative parties.

In Gordon and Buchan (where the Conservatives nominally held a majority of 878 seats), postal return rates fell by just 0.4 percentage points, a decrease of less than 80 votes.

In West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine, return rates have actually increased.

In North Aberdeenshire and East Moray, where the SNP won by 942 votes from the Conservatives, the return fell by three percentage points to 580 votes.

After all, there were some precincts where the number of mail-in ballots returned dropped so significantly that it affected the outcome.

But there is no evidence about how these people voted, or whether their vote differed significantly from that of the broader electorate in the district.

What are the chances that nearly all of those votes went to the one party that needed them, as opposed to the rest of the constituency?

Take the notable example of the London constituency of Putney, where over 6,500 votes were inexplicably excluded from the results published that night due to a “spreadsheet error”, yet when those votes were eventually counted they were classified in the same way as the rest of the constituency, simply increasing Labour’s majority.

It’s also unclear whether holidays were what reduced the rate of returned mail.

Overall voter turnout fell sharply, and disgruntled voters expressed their discontent with the political class at large.

And mail responses appear to track overall participation to some extent.

In Scotland, voter turnout in the 2015 general election was 71.1%, but fell to 66.4% in the first election in 2017, a drop of 4.7 percentage points.

Meanwhile, postal voter turnout fell from 86.6% to 82.9%, a drop of 3.7 percentage points.

Then, as overall participation recovered to 68.1% in 2019, the return rate of mail also increased slightly to 83.1%.

Therefore, given the fairly significant drop in overall voter turnout this time (down to 59.2% in Scotland), it is quite possible that voter apathy is also being reflected in postal voting.

It’s also possible that low attendance rates aren’t just due to school holidays.

Turnout in Scotland fell by 8.4%, slightly more than the 7.4% fall in seats in England, but in Wales, turnout fell by 10.4%, even though the term is still on.

The decline in support is likely due in large part to negative feelings voters have towards all politicians, which is a much more important issue that political parties need to address.

Consider this: Edinburgh North and Leith were tied for the biggest drop in voter turnout in Scotland at 13.6 percentage points, but the number of postal ballots returned fell by just 1.22 percentage points.

When debating why the SNP lost the seat, we might be more concerned about the 9,656 more voters who did not turn up to the polls compared to 2019 than about the 224 fewer postal voters.

Or they might look at places like north-east Glasgow, where more than half of voters did not turn out to vote.

Similarly, when considering why the outgoing Conservative leader Douglas Ross was defeated in his Aberdeenshire North and Moray East constituencies, he may be more preoccupied with the 5,562 votes cast for Reform UK than the 580 that may have been found in the postal ballot.

Those who missed out on the vote should obviously be taken seriously, and the parliament and the electoral commission are seeking to learn lessons for future polls.

However, the controversy over postal voting does not appear to have had a decisive impact on the outcome.