A coalition of the French left won the most seats in high-stakes legislative elections Sunday, according to near-final results, beating back a far-right surge but failing to win a majority. The outcome left France facing the stunning prospect of a hung parliament and threatened political paralysis in a pillar of the European Union and Olympic host country.

That could rattle markets and the French economy, the EU’s second-largest, and have far-ranging implications for the war in Ukraine, global diplomacy and Europe’s economic stability.

In calling the election on June 9, after the far-right surged in French voting for the European Parliament, Macron said sending voters back to the ballot boxes would provide “clarification.”

On almost every level, that gamble appears to have backfired. Results so far showed France plunged into a political fog, with the three main blocs — a leftist coalition, the far-right National Rally and Macron’s centrists — all falling well short of the 289 seats needed to control the 577-seat National Assembly.

“Our country is facing an unprecedented political situation and is preparing to welcome the world in a few weeks,” said Prime Minister Gabriel Attal, who plans to offer his resignation on Monday.

With the Olympics looming, he said he was ready to stay at his post “as long as duty demands.” Macron has three years remaining on his presidential term.

Jean-Francois Badias / AP

Attal made clearer than ever his disapproval of Macron’s shock decision to call the election, saying “I didn’t choose this dissolution” of the outgoing National Assembly, where the president’s centrist alliance used to be the single biggest group, albeit without an absolute majority. Still, it was able to govern for two years, pulling in lawmakers from other camps to fight off efforts to bring it down.

The new legislature appears shorn of such stability. With most ballots counted, the leftist coalition was leading Macron’s centrist alliance, with the far right in third. That confirms the picture also given by pollsters’ projections.

In Paris’ Stalingrad square, supporters on the left cheered and applauded as projections showing the alliance ahead flashed up on a giant screen. Cries of joy also rang out in Republique plaza in eastern Paris, with people spontaneously hugging strangers and several minutes of nonstop applause after the projections landed.

Marielle Castry, a medical secretary, was on the metro in Paris, when the projections were first announced.

“Everybody had their smartphones and were waiting for the results and then everybody was overjoyed,” said the 55-year-old. “I had been stressed out since June 9 and the European elections. … And now, I feel good. Relieved.”

In a statement earlier Sunday from his office, Macron indicated that he wouldn’t be rushed into inviting a potential prime minister to form a government. It said he was watching as results came in and would wait for the new National Assembly to take shape before taking “the necessary decisions,” all while respecting “the sovereign choice of the French.”

A hung parliament with no single bloc coming close to getting the 289 seats needed for an absolute majority in the National Assembly, the more powerful of France’s two legislative chambers, would be unknown territory for modern France.

Mohammed Badra / AP

Unlike other countries in Europe that are more accustomed to coalition governments, France doesn’t have a tradition of lawmakers from rival political camps coming together to form a working majority.

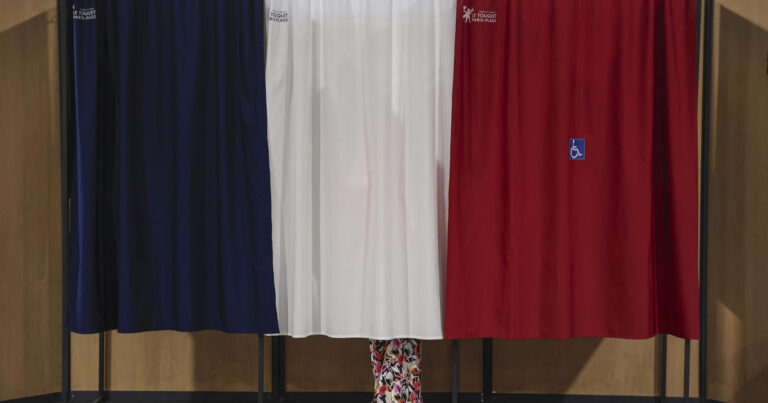

Voters at a Paris polling station were acutely aware of the far-reaching consequences for France and beyond.

“The individual freedoms, tolerance and respect for others is what at stake today,” said Thomas Bertrand, a 45-year-old voter who works in advertising.

Racism and antisemitism have marred the electoral campaign, along with Russian cybercampaigns, and more than 50 candidates reported being physically attacked — highly unusual for France. The government deployed 30,000 police on voting day.

The heightened tensions come while France is celebrating a very special summer: Paris is about to host exceptionally ambitious Olympic Games, the national soccer team reached the semifinal of the Euro 2024 championship, and the Tour de France is racing around the country alongside the Olympic torch.

Reflecting the high stakes, people turned out in large numbers not normally seen for a legislative election, after decades of deepening voter apathy for such votes and, for a growing number of French people, politics in general. As of 5 p.m. local time, turnout was at 59.7%, according to France’s Interior Ministry, the highest at that time in the voting day since 1981. During the first round, the nearly 67% turnout was the highest since 1997.

Pierre Lubin, a 45-year-old business manager, was worried about whether the elections would produce an effective government.

“This is a concern for us,” Lubin said. “Will it be a technical government or a coalition government made up of (various) political forces?”

Laurent Cipriani / AP

No matter what happens, Macron’s centrist camp will be forced to share power. Many of his alliances’ candidates lost in the first round or withdrew, meaning it doesn’t have enough people running to come anywhere close to the majority he had in 2017 when he was first elected president, or the plurality he got in the 2022 legislative vote.

Both would be unprecedented for modern France, and make it more difficult for the European Union’s No. 2 economy to make bold decisions on arming Ukraine, reforming labor laws or reducing its huge deficit. Financial markets have been jittery since Macron surprised even his closest allies in June by announcing snap elections after the National Rally won the most seats for France in European Parliament elections.

Regardless of what happens, Macron said he won’t step down and will stay president until his term ends in 2027.

Many French voters, especially in small towns and rural areas, are frustrated with low incomes and a Paris political leadership seen as elitist and unconcerned with workers’ day-to-day struggles. National Rally has connected with those voters, often by blaming immigration for France’s problems, and has built up broad and deep support over the past decade.

Le Pen has softened many of the party’s positions — she no longer calls for quitting NATO and the EU — to make it more electable. But the party’s core far-right values remain. It wants a referendum on whether being born in France is enough to merit citizenship, to curb the rights of dual citizens, and to give police more freedom to use weapons.

With the uncertain outcome looming over the high-stakes elections, Valerie Dodeman, a 55-year-old legal expert said she is pessimistic about the future of France.

“No matter what happens, I think this election will leave people disgruntled on all sides,” Dodeman said.